To thrive or even survive in our Uncertain World requires creativity, empowerment and collaboration – but most of all equity. We learned this in developing Bristol’s Resilience Strategy and is strikingly evident now as we grapple with global pandemic.

********************

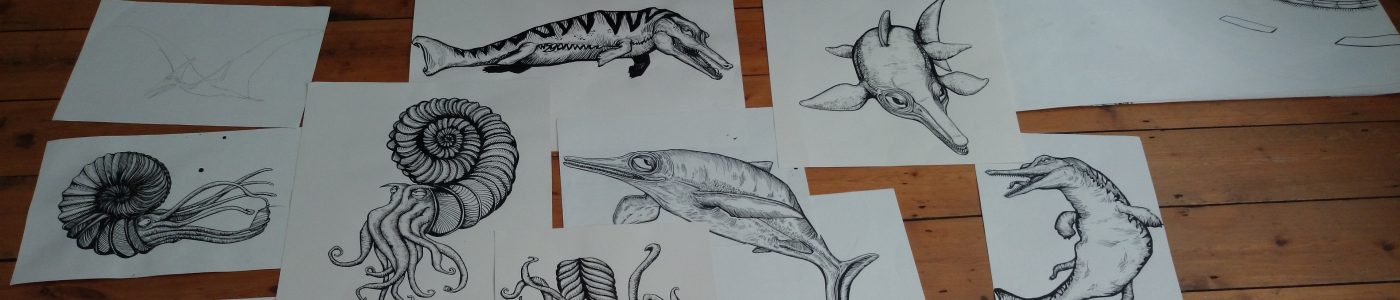

In Bristol, a Plesiosaur and other prehistoric creatures cavort on the weathered side of an Edwardian building, the wall flooded with blue, the animals hovering over the traffic-crowded roads. In the corner of the artwork by Alex Lucas are the words ‘The Uncertain World’ in a font torn from a 60s disaster novel. The prehistoric creatures, from a time when the world was hotter, sea levels higher and the life much different, have been juxtaposed with modern buildings and cars and are meant to be a starting point for conversations about climate change, our past and our future.

It was painted in 2015, when Bristol was the European Green Capital and a focus for dialogue co-curated by the University of Bristol’s Cabot Institute for the Environment, which had long sought to build diverse communities to understand ‘Living with Uncertainty.’

An Uncertain World is an apt description for today, as we face not only the long-term chronic uncertainty of climate change and wider environmental degradation but the acute uncertainty of a global pandemic and economic chaos.

But the issues and maybe the solutions – as many have already noted – are remarkably similar.

From Coronavirus we will learn what we are capable of to stop a global disaster. We will rethink what we are capable of achieving – as individuals, businesses, communities and nations.

We can also learn how to live with the challenging uncertainty that will come with even modest climate change.

In 2015, we aspired to use past climate research to create a more reflective consideration of action, resilience and adaptation. Such research explores the climate and life associated with ancient hot climates, potential analogues for our future. Those long-ancient climates contribute to our understanding of an uncertain future by reinforcing what we do know: when CO2 goes up, so does temperature.

It also shows the limitations of our own personal experiences and understanding. It reveals, for example, that that pCO2 levels have not exceeded 400ppm for ~3 million years; that the current rate of climate change is nearly without precedent; and that ancient rapid warming has dramatic but complex consequences.

In short, it shows us just how unprecedented the world we are creating is.

But perhaps most importantly, it provides for us the otherwise absent personal and societal narratives of climate change. None of us have experienced this Uncertain World. Nor has our civilisation. Not even our species. Therefore, the geological past creates a space for considering what unprecedented really means, for considering living with not a statistical uncertainty but a deep uncertainty, an uncertainty that is not informed by our individual, familial, societal or even civilisation experiences.

So perhaps it is not surprising that our conversations entirely predicted the debates we are now having daily about how to address the Covid-19 emergency, and in particular the lack of consensus about how to act when we have no shared experience on which to draw.

Unlike the current passionate debate about pandemic (and climate) action, however, the Uncertain World also allowed us to relocate discussion away from modern divisive politics to the ancient past and unknown futures, thereby creating a place of reflection. Through this, we collaboratively explored what we know or do not about our past and future, renewing motivation for climate action. But perhaps most importantly, by focusing on the uncertainty in the Earth system, we explored the creative forms of resilience that will be required in the coming century (Cabot Institute Report on Living with Environmental Uncertainty.pdf). And all of this contributed to the creation of Bristol’s Resilience Strategy (Bristol Resilience Strategy-2n5wmn3) and then its One City Plan.

And the findings from those discussions are identical to what we are learning today: equity must be at the centre of any society that hopes to withstand the shocks of uncertainty.

In our conversations, we as a City identified five principles that must shape our resilience. Society must be liveable, agile, sustainable and connected. And most of all, fair. Although we might choose different words in the fire of a pandemic, the principles are fundamentally the same as those we debate right now. Of course, we aspire to live – and not just to live but to enjoy life and have a high quality of life. But to do so, we must live and act sustainably and within the means of ourselves, our families, our society and our planet. The Covd-19 crisis is acutely showing what we really value to enjoy life, the differences between what we think we need and what we really need; and in doing so, it is showing us new pathways to sustainability.

To thrive in an uncertain world, we must also be agile. And that means that we must be flexible and creative and have the power to act on those creative impulses and innovative ideas. Some agility can come from centralised government and sometimes it must, such as the decisions to close some businesses and financially support their vulnerable employees; build new hospitals; and repurpose factories to make ventilators. However, the agility that is often the most effective for dealing with the specifics of a crisis arise from our communities and individuals. That requires a benevolent sharing of power – not just political but economic. Communities need the resources to decide how to manage floods and food shortages locally – and the decision-making political power to act on those. Likewise, we need the power and resources to support our vulnerable neighbours during a pandemic, and to support the local businesses and their employees struggling to survive an economic shutdown.

The counterpoint to agility – of an individual, community or nation – is connectivity. We cannot adapt and thrive and survive on our own. The individual who builds a fortress will soon run out of food. Or medicine. Or entertainment. The nation that disconnects from others will find itself in bidding wars for ventilators and vaccines. And perhaps eventually resources and food,

Inevitably though, every single resilience or adaptation or preparedness conversation leads to fairness; to equity and inclusion. The wealthy have power, agency and agility. The wealthy have the means to build a fortress while remaining connected. The wealthy can stockpile food. They can hire equipment to build flood walls around their estates. They can flee famines and cross borders.

They can flee pandemic.

They can choose how they work. Or whether to work.

They can access virus tests long before the rest of us.

The bitter irony is that we have learned from the Covid-19 crisis what we always knew: that those who are often the least respected, the least paid, the most vulnerable are the most essential. They are the ones who harvest our food and get it to our stores and homes. They work the front lines of the health services. They are the ones who keep the electricity and water operating. And the internet that allows University Professors to work while self-isolating.

And the poorest in our societies will die because of it.

The same will be true of the looming climate change disaster – but more slowly and likely far worse. It will come first through heat waves that in some parts of the world make it impossible to work; through extreme climate events that devastate especially the most vulnerable infrastructure. And then it will devastate food production and global food supply chains. It will displace millions, at least tens of millions due to (the most optimistic estimates) of sea level rise alone, and then potentially hundreds of millions more due to drought and famine.

Who will suffer? Those who must labour in the outdoor heat of fields and cities. Those who are already suffering food poverty. Those who cannot flee across increasingly rigid borders from a rising sea or a famine. Climate change is classist and it is racist. It is genocide by indifference.

And unlike a pandemic, the wealthy cannot simply wait out climate change. They will either succumb to the same crumbling structures as the rest of us; or they will be forced to entrench their power via ever more extreme means. There is a reason why nearly every dystopian story is ultimately a story about class struggle.

But we can address that if we are learn the lessons of today and elevate the values of equity and community that make us stronger together. And if we build societies that embody those values – societies that recognise that prosperity is not a zero sum game. We can horde or we can share food on a world where less is produced. We can leave everyone to themselves or guarantee people a home and an income. We can put up walls or tear them down. We can sink boats carrying refugees or we can build them. Coronavirus has exposed the inequities in our society, but it has also shown that we can end them if the desire is great enough. And in that, there is hope.

A resilient world, a strong world, a world that will survive this pandemic and that will survive the coming climate catastrophes must more than anything be an equitable world. There is no reason for it not to be.