We have two exciting PhD Opportunities (starting Oct 2023 but flexible) as part of CERES!!

(Note that these are UKRI funded and therefore primarily aimed at UK applicants, but exceptional international applicants can be considered)

CERES Project Background

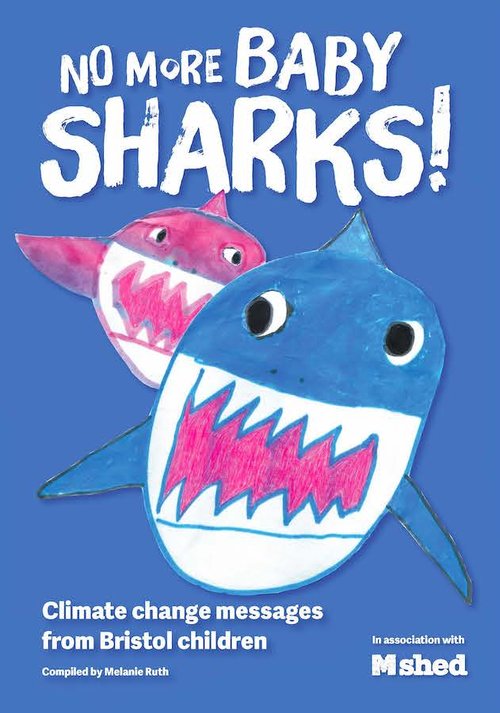

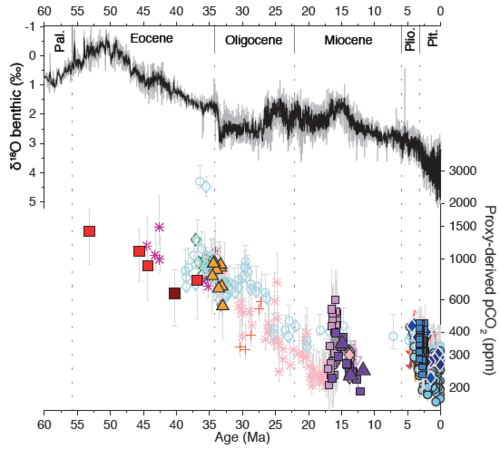

Microbial processes in terrestrial settings are critical to governing greenhouse gas emissions. The modern carbon soil reservoir exceeds that of terrestrial vegetation and the atmosphere combined, and soil microorganisms annually cycle 1/3 of the carbon photosynthesised and account for the largest natural methane flux to the atmosphere. In doing so, they govern the chemical and climatic state of our planet. And yet these processes remain poorly understood as they are mediated by a range of environmental factors. Insight can be derived from geological archives that document the responses of biogeochemical systems to past environmental perturbations across a range of timescales from 1000s to millions of years. Our previous studies on peat and lignites provide tantalising insights into climate-driven disruption of the carbon cycle, but the underlying mechanisms remain unresolved. This PhD, as part of the wider CERES project, will address that by exploring the organic geochemistry of peatlands that have undergone radical transformation – from drying and degradation to restoration to flooding.

PROJECT TITLE: Fates of peatland carbon under different nutrient regimes

Lead Institution: University of Bristol, School of Earth Sciences and School of Chemistry

Lead Supervisor: Dr Casey Bryce, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol

Co-Supervisor: Professor Rich Pancost, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol

Other Co-Supervisors: Professor Angela Gallego-Sala; Geography, University of Exeter; Dr David Naafs, School of Chemistry, University of Bristol; Dr Heather Buss, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol

Project Enquiries: casey.bryce@bristol.ac.uk or r.d.pancost@bristol.ac.uk

Project Aims and Methods:

Peatlands are sensitive responders to and recorders of climate and environmental change. They play a crucial role in the global carbon cycle via the burial of organic carbon and the production of methane. Most work has focused on temperate and subarctic peatland, but recent work including our own pilot analyses suggests that tropical peatland carbon cycling and the associated bacterial and archaeal communities could be markedly different. Higher temperatures, higher nutrient concentrations and more woody (and lignin-rich) biomass will all impact the pathways by which organic matter is recycled and degraded.

We will explore and compare environmental and biogeochemical disruptions in Welsh, English, Swedish, Panamanian and Colombian peatlands (and potentially peatlands from Uganda, the DRC and Papua New Guinea). The specific sites and time intervals will be developed in collaboration with the PhD student and the supervisory team, but we are particularly interested in comparing and contrasting the microbial pathways of organic matter preservation/decomposition under different nutrient regimes. Under some nutrient replete conditions, for example, nitrate and Fe could serve as electron acceptors – contributing to anaerobic organic matter degradation, mitigating methanogenesis and serving as oxidants in the anaerobic oxidation of methane. We will determine how different nutrient conditions and different climatic regimes give rise to different microbial communities, organic matter preservation and organic matter composition. This knowledge will vastly improve our understanding of how microorganisms dictate the climatic impacts of peatland perturbations now and in Earth’s history.

Background reading and references

Ritson JP, Alderson DM, Robinson CH, Burkitt AE, Heinemeyer A, Stimson AG et al. Towards a microbial process-based understanding of the resilience of peatland ecosystem service provisioning – A research agenda. Science of the Total Environment. 2021 Mar 10;759. 143467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143467

Patzner, M.S., Logan, M., McKenna, A.M. et al. Microbial iron cycling during palsa hillslope collapse promotes greenhouse gas emissions before complete permafrost thaw. Commun Earth Environ 3, 76 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00407-8

Pancost, R.D., Sinninghe Damsté, J.S., 2003, Carbon isotopic compositions of prokaryotic lipids as tracers of carbon cycling in diverse settings. Chem Geol 195: 29-58.

PROJECT TITLE: The Organic Geochemistry of Peat in Transition

Lead Institution: University of Bristol, School of Earth Sciences and School of Chemistry

Lead Supervisor: Professor Rich Pancost, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol

Co-Supervisor: Dr David Naafs, School of Chemistry, University of Bristol

Other Co-Supervisors: Dr Casey Bryce, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol; Professor Angela Gallego-Sala; Geography, University of Exeter

Project Enquiries: r.d.pancost@bristol.ac.uk

Project Aims and Methods:

Peat and lignite deposits have long been used to explore past changes in climate, especially changes in temperature and precipitation. However, peat deposits can also document the biogeochemical responses to those environmental changes. To explore these, a wide range of approaches have been developed based on changes in the bulk composition of peat, transformations in specific environmentally sensitive biomolecules and tracers for specific microbial communities. However, they have been developed and applied to a relatively narrow range of relatively unaltered temperate and subarctic peatlands. This project will focus on a range of peatlands that have experienced dramatic transformations, including drainage, drying and restoration and from a range of climate regimes from the Arctic to the Tropics.

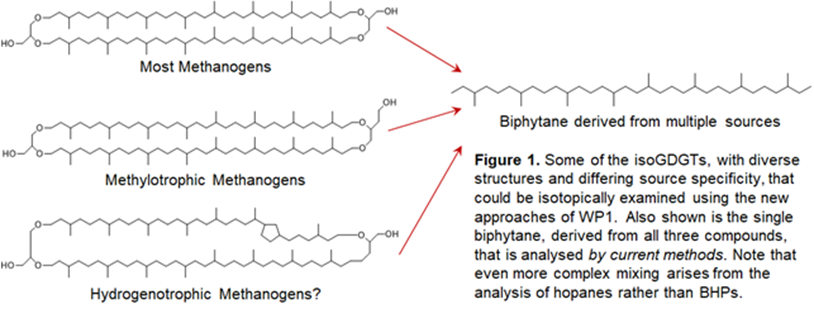

We will explore and compare environmental and biogeochemical disruptions in Welsh, English, Swedish, Panamanian and Colombian peatlands (and potentially peatlands from Uganda, the DRC and Papua New Guinea). The specific sites and time intervals will be developed in collaboration with the PhD student and the supervisory team, but we are particularly interested in documenting sites that have experienced drying, drainage and restoration, allowing us to explore the biomolecular signature of disruption as well as its persistence. We will determine how these disruptions affected rates of carbon accumulation and the overall chemical composition of the peat, as well as the associated microbial communities that are involved with its stepwise degradation to simpler substrates and eventually CO2 and methane. Working with the wider CERES team, the PhD student will apply new lipidomic techniques, especially those arising from the distribution of unusual archaeal and bacterial membrane lipids, to ascertain the relationships between past changes in peatland hydrology, microbial metabolism, and carbon cycling.

Background reading and references

Huang, X. et al., 2018, Response of carbon cycle to drier conditions in the mid-Holocene in central China. Nature communications 9, 1369.

Inglis, G.N. et al., 2019, d13C values of bacterial hopanoids and leaf waxes as tracers for methanotrophy in peatlands. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 260, 244-256.

Pancost, R.D., Sinninghe Damsté, J.S., 2003, Carbon isotopic compositions of prokaryotic lipids as tracers of carbon cycling in diverse settings. Chem Geol 195: 29-58.

Information for both posts

Candidate requirements

The Organic Geochemistry Unit (OGU) and the Biogeochemistry Group in earthhas a long history of interdisciplinary research; as such, we host intellectually diverse applicants, welcoming your new perspectives into our lab and our obligation to train you in the methods you will use. Similarly, we welcome and encourage student applications from minoritized and marginalised and value a diverse research environment. Funding is available for UK students, but exceptional international students can also be considered.

Project partners

This project builds on a long-standing Bristol-Exeter collaboration in which we have developed and applied new approaches to understanding peatland processes. We also have collaborations in Wales, Sweden, Colombia and Panama, ensuring access to samples and sites

Training Opportunities

As part of CERES, there will be outstanding opportunities for field work and associated training. We recognise the constraints field work imposes on applicants from some backgrounds, however, and field work is not mandatory (with samples provided by partners). The PhD focuses on geochemical and microbiological investigation of peat, including characterisation of microbial communities, bioavailable nutrients, organic matter composition and greenhouse gas fluxes. The Earth Sciences Biogeochemistry and Geomicrobiology labs have fantastic facilities and opportunities for training in both culture-dependent and culture-independent microbiology and geochemistry whilst the OGU has a long track record of providing training in organic geochemistry to diverse students from all backgrounds. Successful applicants will also be able to access the extensive transferable skill training associated with the NERC GW4+ Doctoral Training Partnership, as well as those of Bristol’s Doctoral College.

Useful links

To apply: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/earthsciences/courses/postgraduate/

For information on the OGU: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/chemistry/research/ogu/

For information on CERES: https://richpancost.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/2022/09/11/ceres-climate-energy-and-carbon-in-ancient-earth-systems/

How to apply to the University of Bristol:

http://www.bristol.ac.uk/study/postgraduate/apply/

The application deadline is 3 MARCH; Interviews will take place during the period 13 to 23 March, 2023. The preferred start date will be Oct 2023 but the funding of the project allows flexibility

Funding is available for 3.5 years at standard UKRI rates.