Cabot Institute Director Professor Rich Pancost will be attending COP21 in Paris as part of the Bristol city-wide team, including the Mayor of Bristol, representatives from Bristol City Council and the Bristol Green Capital Partnership. He and other Cabot Institute members will be writing blogs during COP21, reflecting on what is happening in Paris, especially in the Paris and Bristol co-hosted Cities and Regions Pavilion, and also on the conclusion to Bristol’s year as the European Green Capital. Follow #UoBGreen and #COP21 for live updates from the University of Bristol.

Part 4

—————————–

For the past two days, a delegation of us have been representing Bristol City Council and a group of Bristol businesses at the Sustainable Innovation Forum (SIF) at Paris. Our group included Bristol Mayor George Ferguson, who spoke on Tuesday; Amy Robinson, of Low Carbon Southwest and the driver behind the Go Green business initiative; Bristol City Council representatives Stephen Hillton and Mhairi Ambler; and Ben Wielgus of KPMG and Chris Hayes of Skanska, both Bristol Green Capital sponsors.

This was the COP21 ‘Business event’ and aspects of this have been rather sharply targeted by Paris activists. There is a legitimate question of whether corporate sponsors are engaging in greenwashing, but this was not my perception from inside Le Stade de France. There were some major fossil fuel dependent or environmentally impactful companies in attendance, but they seemed genuinely committed to reducing their environmental impact. Their actions must be transparent and assessed, and like all of us, they must be challenged to go further. This is why it was fantastic that Mindy Lubber, President of Ceres, was speaking. Ceres is a true agent of change, bringing a huge variety of businesses into the conversation and working with them to continually raise ambition.

The majority of these businesses, just like those that attended Bristol’s Business Summit in October, are clearly and objectively devoted to developing new technologies to address the world’s challenges,. Whether it be new solar tech that will underpin the PVC of 2050 or innovative new ways to deploy wind turbines cheaply and effectively in small African villages, it is no longer ‘business’ that is holding back climate action and in many cases they are leading it.

And we need them to do so. We need them to develop new products and we need them to be supported by government and Universities. We need them because we need new innovation, new technology and new infrastructure to meet our environmental challenges.

One of the major themes of the past two days has been leadership in innovation, an ambition to which the University of Bristol and the City of Bristol aspires – like any world-class university and city. We have profound collective ambitions to be a Collaboratory for Change. These are exemplified by Bristol is Open, the Bristol Brain and the Bristol Billion, all endeavours of cooperation between the University of Bristol and Bristol City Council and all celebrated by George Ferguson in his speech to the SIF attendees yesterday.

This need for at least some fundamentally new technology is why the Cabot Institute has launched VENTURE. It is why the University has invested so much in the award-winning incubator at the Engine Shed. It is why we have devoted so much resource to building world-leading expertise in materials and composites, especially in partnership with others in the region.

We do not need these innovations for deployment now – deployment of already existing technology will yield major reductions in our carbon emissions – but we need to start developing them now, so that we can achieve more difficult emissions reductions in 20 years. Our future leaders must have an electrical grid that can support a renewable energy network. Our homes must have been prepared for the end of gas.

And we will need new technology to fully decarbonise.

We effectively have no way to make steel without burning coal to melt iron – we either need new tech in recycling steel, need to move to a post-steel world, need to completely redesign steel plants, or some combination of all three.

We will need new forms of low-energy shipping. Localising manufacturing and recycling could create energy savings in the global supply chain. But we will always have a global supply chain and eventually it must be decarbonised.

Similarly, we will need to decarbonise our farm equipment. At heart, I am still an Ohio farm boy, and so I was distracted from my cities-focus to discuss this with Carlo Lambro, Brand President of New Holland. Their company has made some impressive efficiency gains in farm equipment, especially with respect to NOx emissions, but he conceded that a carbon neutral tractor is still far away – they require too much power, operating at near 100% capacity (cars are more like 20-30%). He described their new methane-powered tractor, which could be joined up to biogas emissions from farm waste, but also explained that it can only operate for 1.5 hours. There have been improvements… but there is still a long way to go. I appreciated his engagement and his candor about the challenges we face (but that did not keep me from encouraging him to go faster and further!).

Finally, if we really intend to limit warming to below 2C, then we will likely need to capture and store (CCS) some of the carbon dioxide we are adding to the atmosphere. Moreover, some of the national negotiators are pushing for a laudable 1.5C limit, and this would certainly require CCS. In fact, the need for the widespread implementation of such technology by the middle of this century is explicitly embedded in the emissions scenarios of IPCC Working Group 3. That is why some of our best Earth Scientists are working on the latest CCS technology.

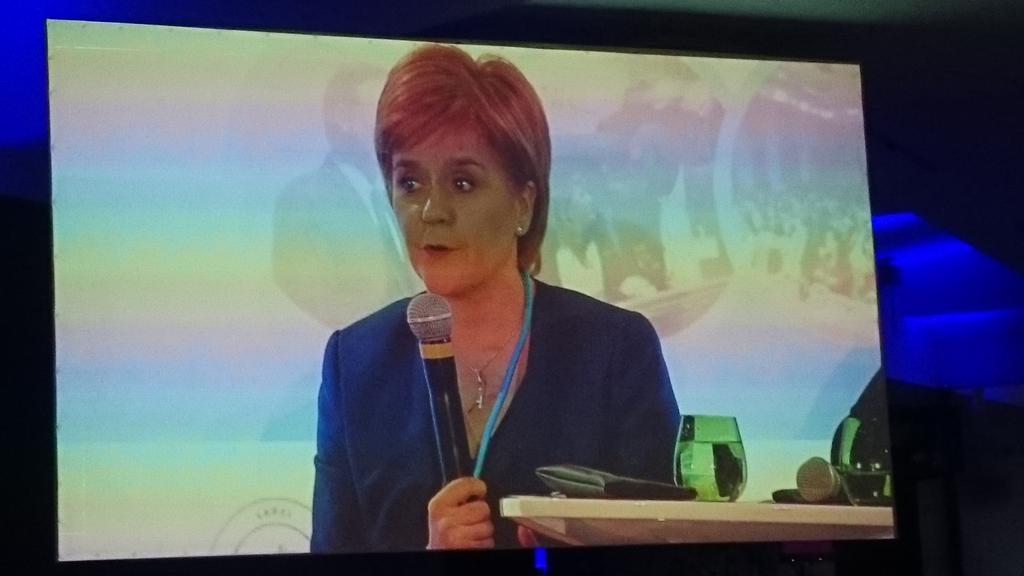

Unfortunately, CCS illustrates how challenging innovation can be – or more precisely, as articulated by Californian entrepreneur Tom Steyer, how challenging it can be to develop existing technology into useful products. The CCS technology exists but it is still nascent and economically unviable. It must be developed. Given this, the recent cancellation of UK CCS projects is disappointing and could prove devastating for the UK’s intellectual leadership in this area. The consequences of this decision were discussed by Nicola Sturgeon in a panel on energy futures and she renewed Scotland’s firm commitment to it.

This issue exemplifies a wider topic of conversation at the SIF: social and technological innovation and development requires financing, but securing that financing requires safety. Skittish investors do not seek innovation; they seek safe, secure and boring investment. And SIF wrapped up by talking about how to make that happen.

First, we must invest in the research that yields innovations. We must then invest in the development of those innovations to build public and investor confidence. Crucial to both of those is public sector support. This includes Universities, although Universities will have to operate in somewhat new ways if we wish to contribute more to the development process. We are learning, however, which is why George Ferguson singled out the Engine Shed as the world’s leading higher education based incubator.

Second, and more directly relevant to the COP21 ambitions, businesses and their investors need their governments to provide confidence that they are committed to a new energy future. It has been clear all week that businesses will no longer accept the blame for their governments’ climate inaction.

Instead, most businesses see the opportunity and are eager to seize it. As for the few businesses that cling to the past? Like all things that fail to evolve, the past is where they shall remain. The new generation of entrepreneurs will see to that. Whether it be the new businesses with new ideas or the old businesses that are adapting, the new economy is not coming; it is already here.