This commentary is an expansion on my presentation at the 2022 session on Scientific Neocolonialism.

Thank you to EGU for creating the space for this vital conversation, to the organisers and to my fellow speakers, and to all of you for coming.

I would like to start with a statement on positionality. I have white privilege. Male privilege. Cishet privilege. I did grow up in rural poverty; we were farmers and we were poor, and I was a first generation University student. But I did have access to education, and I certainly am no longer working class, no matter how deep the roots may be. Perhaps of equal importance is my institutional privilege. I work in a discipline – the geosciences generally and organic geochemistry specifically – that has been built on a legacy of exploitation and extraction; and I work for a relatively stable and secure University that inherited and built – and arguably still builds – its wealth on the back of colonial practices.

As such, I was invited by the organisers to use that privileged position to speak honestly and forthrightly about the historical and ongoing failings of our discipline. And to acknowledge my own failings.

I do, however, have some ambivalence about participating. I think it is the obligation of those with privilege – especially those like myself – to do the labour, especially the risky and emotionally taxing labour in talking about difficult topics. However, I also recognise that in doing so, I am occupying a seat that might have been better filled by someone who lacks my privilege and would benefit from this platform.

Am I creating space? Or occupying space?

I’ll return to this. And it is an important theme that has pre-occupied me in every role I have taken – from accepting or declining conference invitations to joining NERC’s Science Committee to becoming Head of School . But for now let me say to my colleagues who share my privilege ‘get use to this feeling of discomfort and learn to live with it.’ This discomfort is essential to the decolonial efforts, as is taking any criticism with dignity.

**********************************************************

I am not an expert; I am a geochemist. Like many of us who are struggling with the colonial aspects of the Earth Sciences, I am here as one who has not done as well as I should, wants to do better, and expects all of us – especially the senior leaders of the field – to do the same. However, I have been fortunate enough to learn from colleagues across disciplines. Due to the dearth of expertise in STEM subjects I have often been invited to serve on panels such as these, including the NERC/AHRC Hidden Histories Advisory Group and Bristol’s Decolonising the Curriculum Working Group. I have also learned from more grass roots radical movements at the University of Bristol, from staff who demand our institution more actively confront its colonial legacies. In all of these, I have tried to be honest about the limitations of my expertise, my genuine desire to learn and my commitment to sharing what I learn from the actual experts.

And the one thing that I have learned is that the legacy of colonialism is pervasive, and that our decolonisation journey will be long and challenging. And necessary. @Jairo_I_Funez is a powerful scholar in this space and I hope he does not mind me borrowing a quote of his from Twitter: ‘In practice, the world isn’t divided in silos: colonial, racist, capitalist, & patriarchal silos. These are entangled & distinctly expressed according to geography. Analytically we can try to separate them but in reality they are entangled systems of domination and exploitation. People seem to really want straightforward manuals for this stuff but that in itself is part of the problem. It isn’t simple or fair because reality isn’t simple or fair.”

So let us talk about the entangled systems of domination and exploitation, in my own career and in our discipline.

**********************************************************

I owe a lot to my supervisors and colleagues who helped set me on a strong path during my PhD training. They taught me to respect other disciplines and expertise, in particular warning me away from scientific hubris and thinking that my new fancy analytical toy can solve the problems that others have struggled with for decades. Or if we do solve them, to acknowledge that we could not have done so without that previous labour. Building from that, it is inescapable that we recognise that science is a community, with the vast majority of successes achieved not by a single genius but by a community of scholars who sometimes argue but always centre a constructive and collaborative approach to building knowledge. This is particularly true of the Earth Sciences, where we must collaborate to drill a core through an ice sheet, send a seismometer to Mars, or build a decades long field campaign.

But this inevitably demands that we ask “who is that community?” Our discipline has been profoundly guilty of helicopter or parasitic science, sometimes cynically so and sometimes with good intentions. But regardless of the motivations, it excludes scholars from the global south, marginalised groups and indigenous peoples. Robyn Pickering spoke powerfully about this in her presentation. So here I want to share that I have made these same mistakes.

You can look through my publication record and find many examples of these: collaborations with New Zealand colleagues that failed to acknowledge the Māori peoples on whose occupied land we worked; collections of samples from exotic locations with which I calibrated palaeoclimate proxies but failed to include local collaborators. Perhaps the most striking example is my work on arsenic contamination in Cambodian aquifers; this is work that I am very proud of as it helped resolve the biogeochemical mechanisms underpinning As mobilisation. But our earliest work included no local collaborators, to the detriment of the science, to the detriment of the uptake of our findings, to the detriment of colleagues in Cambodia working on these issues. [I no longer work in this area, having ‘passed the baton’ to my postdoc who is now at Manchester, but I am glad to see that this group now works in thriving collaboration with Cambodian colleagues.]

There have been times that I have engaged more appropriate practice in terms of collaboration and co-production. Our palaeoclimate work in Tanzania featured strong collaborations with Tanzanian geoscientists, especially the wonderful Joyce Singano. In doing so, funding was passed from the UK to Tanzania and prestige was shared, benefitting their careers and their institutions. This is not theoretical – these decisions have real and immediate consequences and impacts. So why do we not do it all the time? I have been as guilty as anyone of using the argument that ‘there are no scholars in that area in this country’, but surely that should prompt a number of questions: i) how hard have we really looked; ii) if not, then should we not have a long-term vision of collaboratively building that community; iii) should we not work in an area or a topic if we cannot do it equitably and inclusively?

But I suspect that much of our current neocolonial practices arise from naivety. We just do not think about these issues. But naivety is not an excuse for those of who work in institutions of wealth and privilege, are funded by intuitions of wealth and privilege, and work in countries made wealthy by colonial exploitation. We cannot afford the luxury of being ignorant of our power and influence.

I think that helicopter or parasitic science is the most obvious manifestation of neocolonial practices that persist in our discipline. However, decolonisation is an act of continual reflection, self-critique and learning and that means understanding the complexities in even some superficially strong local collaborations. I increasingly work with scholars in Panama and Colombia, but often those scholars are part of their own nations’ colonial legacies with their own problematic relationships with indigenous peoples. Complex legacies of colonialism persist in Africa. Geopolitical complications haunt my collaborations with China, especially in places such as Tibet.

Having said that, I am drifting dangerously close to whataboutery, and I refuse to allow that; I raise these issues not for deflection but to set myself on a path towards ever deeper reflection. The complexity of these issues must not stop action today, and there is nothing preventing us from engaging directly with the colonial sins in our own house. (For these reasons, Hidden Histories chose to focus solely on British colonialism.)

**********************************************************

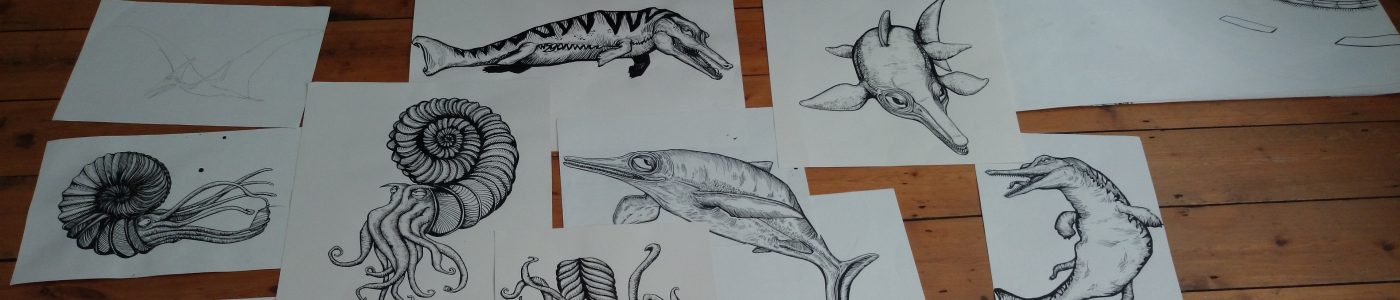

Decolonisation is about more than diversity and inclusivity, although there is certainly a strong connection between our decolonial and EDI efforts and I do not think one can be legitimate without the other. Decolonisation is ultimately about agency and power, and addressing that entails challenging the assumptions deeply embedded in our practice and that of our discipline. Our discipline is based on extraction and exploitation. We pillaged fossils from all over the world, a practice that continues to this day, often in direct violation of the laws of that country. Our discipline can display an appallingly arrogant and patriarchal view towards the Earth and land, often in direct conflict with those who live on it. Mary Anning was funded by the enslavement of people – Henry de la Beche, her sponsor and first President of the Palaeontological Association, was an apalling person who acquired great wealth through his slavery inheritance.

Our entire discipline has been instrumental in the exploitation of fossil fuel and mineral resources and the people who live on that land, and we still are.

We must constantly explore and engage with that. And we certainly must not try to create artificial silos that we pretend can exonerate us from those obligations. I am an organic geochemist, with colleagues, friends and former students who work in the oil and gas sector. I ended my own research collaborations with those industries about 15 years ago – but that was driven by environmental and climate change concerns rather than decolonial ones. This was a dangerously narrow view that elevated some forms of harm over others. If we do not include decolonial aspects in our thinking and our science and our practice, we are going to replicate past harms and perpetuate new inequalities under the banner of biodiversity preservation and renewable energy.

It has become quite trendy in our discipline to talk about the necessity of geology – especially economic and resource geology – to a post-fossil fuel future dependent not on oil but copper, cobalt and lithium. This is true. But we cannot build a green future on green colonialism (and arguably such an effort, in discarding indigenous knowledge, would be doomed to failure).

Moreover, I cannot simply ignore the deep entanglement of my research practice with colonial and neocolonial histories. My techniques were built by my academic predecessors with industry support. I can do what I do because of the investment in organic geochemistry fueled by the global exploitation of oil resources (Chevron built first GC-IRMS) . That extends to so may of us, from biostratigraphy to palaeogeographic reconstructions to palaeontology, all built on global extractivism.

I am not saying that we should not work with industry or you have to be anti-capitalist (but many experts do convincingly argue that view). But I do not see how decolonisation can be compatible with unbridled free marketeering. It certainly is not compatible with uncritical engagement with any industrial partner. I leave that to each of you to discuss where those boundaries lie.

And in doing so, we must be quite open-eyed about the fact that most Western Universities, regardless of their taxation status, operate in a pretty damned capitalist and colonial manner themselves. My own University’s logo contains four symbols – a sun, a ship, a horse and a dolphin – each one of those the symbol of a great family in Bristol that built their wealth entirely or in part by the enslavement of people. That dolphin is the symbol of Edward Colston. But let us not pretend that colonialism is an artefact of the past, ‘Hidden Histories’ alone. My University, like all UK Universities and many across the West, remains financially dependent on exorbitant fees paid by international students; my salary and my lab and my career are funded by the ongoing extraction of wealth from across the world to the University of Bristol.

We must be awake to these issues and engaged with the harms they have caused – and our complicity with them and continued dependence on them.

‘They are entangled systems of domination and exploitation.’

**********************************************************

What can we do? As with many challenges we face, we must recognise the need for structural change. In doing so, we must learn, share and act with a certain degree of kindness for ourselves – all of us are somewhat trapped in these colonial structures. I have colleagues who are seeking research funding from new, less problematic sources who also feel severe institutional pressure to win grants; they feel trapped. As Head of School, I often feel complicit in enabling their entrapment. Collectively, we must demand structural change.

However, just like tackling racism or climate change, the need for structural change does not exempt us from individual responsibility. And of course, our individual actions can collectively and joyfully become a movement that drives that structural change. So here are some suggestions.

Read, listen and learn. Most of us will not become experts in this topic, but we can all devote time to learning. I recognise that we are all overworked, but this is an obligation for our discipline.

Have humility for those who do the work, whether they be geoscientists who choose to focus on this area of those outside the discipline. And then celebrate and reward this work. Liberate time for our colleagues who do devote time to become experts, and recognise this work in their promotions. Pay external experts. Pay marginalised scholars to speak or advise. Pay for their time as we would pay any other consultant.

Accept discomfort and learn from it. Be thoughtful, continuously thoughtful and with intellectual commitment comparable to how we do the rest of our job. Be honest with ourselves. So treat yourselves with kindness. But that is no excuse to not challenge and continuously interrogate ourselves and one another.

Most importantly, collaborate and co-produce knowledge. Work with brilliant and inspiring scholars from all over the world. And although this is an important path to reparation, it is also wonderful and joyous.

Finally, build on your learning and experiences to make that structural change. Demand institutional support – and when you have the privilege to do so, challenge institutional behaviour. Advocate for new policies, from EGU Awards to staff promotions processes to criteria for grants and publications.

**********************************************************

Ultimately, however, we must never forget that this is not an academic exercise. It is part of a wider process of reparation of harm and reconciliation. It must be a dialogue and it must be tangible. Frantz Fanon wrote: “For a colonized people the most essential value, because the most concrete, is first and foremost the land: the land which will bring them bread and, above all, dignity.” These conversations are important for our field, but they do not stop colonised people from being exploited, robbed or killed. Our work must ultimately commit to an agenda that restores wealth, respect and dignity. And by extension, it must restore stolen agency and power, because these reparations of harm cannot happen using our current structures: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Given that end goal, was I right person to contribute? Did I make space or occupy space? On reflection, I think it was it a mistake for me to agree to speak at this session rather than advocating for a speaker from a non-Western nation or from a marginalised group. I hope that I’ve moved our conversation forward, but I am not convinced that I was best suited to use this forum to also achieve reparation.

Instead a speaker from the global south or an indigenous speaker could have used this opportunity not only to speak honestly and forthrightly about the challenges they face but also use this as a platform to reclaim some of their scientific agency. They could have come to this EGU session, spoken about decolonization but also talked about their science – their ambitions, their findings and the types of collaborations that would strengthen their careers.

I apologise for occupying that space.

So then, looking towards the next conference or next year, can we all agree that we must do this work and that we do not need someone like me to create this space?

Instead, we should pack this panel with the voices of minoritized and indigenous voices, while also giving them a chance to prominently showcase their science throughout the wider EGU program.

While the rest of us pack this hall to listen to what they have to say.

Some resources:

And for a life-enriching immersion in the topic, please consider Kathryn Yusoff’s ‘A Million Black Anthropocenes or None.’