A few months ago I wrote this, about the challenges of being working class and the obstacles we face in our careers. I wrote that with one purpose – to explain that those of us who have “made it” did so with some intelligence and hard work but mostly luck. I wrote this to dismantle the flawed and perniciaous myths of social mobility and meritocracy.

Today I write not about how us lucky ones got to academia but how it treated us once we arrived, once we’ve “made it”.

That’s the other myth – you never “make it”. The legacy of working class never leaves. It manifests in all sorts of different ways – from overcompensation to forever feeling an outsider. But it persists.

I need to be careful here. The white working class male will certainly pass in academica, and our working class upbringing can eventually fade into an upper middle class income and lifestyle. I might have dodgy teeth and be betrayed by accents or manners, but even working class social awkwardness can be disguised as academic awkwardness.

We can pass.

So let’s not pretend our burdens are the same as black scholars or women or any minoritised group who cannot simply change the nature of their ‘otherness’ in academic circles. Let’s not pretend that working class obstacles persist and shape our careers to the same degree as race and gender and disability, when many of our obstacles are eliminated with job security and a promotion. Let’s not ignore the intersection of those prejudices.

But nevertheless, no matter what happens in your life you never fully escape your origins.

Precarity

The academic career is unusually precarious. Financial precarity amplifies that. Dramatically.

But it is complicated. My meager PhD stipend was actually the most money I had my entire life; for the first time in my life, I had disposable income. For the first time in my life, I could go out to eat and join in social activities. Because I knew how to save money and knew how to get by on inexpensive food or cheap accommodation or was willing to house share, I knew how to make that stipend last.

I was also very lucky in avoiding the precarity of the academic bottleneck between PhD, postdoc and permanent job. I had my post-doc arranged when I finished my PhD; I had procured an assistant professorship post before I finished my post-doc. But I was lucky. I was lucky with those jobs and that job market. I was lucky in that both my PhD and Postdoc supervisors were well-known, respected and well-funded – providing a financial safety net as I navigated the challenging job market. And also, let’s be honest, those academic pedigrees unfairly advantaged me in getting my job at Bristol. I had lucked into the right choices that helped me win a rigged game.

But precarity is real. And is worse now than ever. It takes longer to get a job: more time living under a cloud of uncertainty; more time waiting to buy a home or start a family; more time doing more jobs, different jobs, learning group dynamics, maybe moving- often internationally – with financial and emotional costs. And that means more work, trying to keep up, trying to maintain your ‘productivity’ while figuring out new personalities and friendships, how to order pipettes in a new lab, get a visa or navigate a new country’s rental market. At the same time, contracts seem to be getting shorter, requiring more uncertainty, more movement, more working on papers while unpaid, more exploitation.

The lack of a financial safety net exacerbates all of that. It is harder to move around and follow jobs. It is harder to start a family. It is impossible to wait around between postdoc contracts; instead of writing papers between contracts, you get a job at a cafe. You pay rent rather than paying off a mortgage, ensuring that at least some of that financial precarity follows you your entire life.

But the worst part of that precarity is its emotional toll – the uncertainty, the fear and the fact that so many people in academia do not understand it.

Despite my good fortune, this uncertainty haunted my career. I remember confiding in a trusted mentor, someone who I respect as much as anyone in my life, and they replied: ‘If you’re good, you’ll get a job.’ And as much as I respected them, in that moment I knew there was one chasm they’d never understand, having come from a middle class family of academics. They could have empathy but never truly understand 1st generation fear and 1st generation risk. And they’d never fully understand the one thing that poor people understand perfectly: you can be amazing and still fail.

And whether intentional or inadvertent, whether individual or systemic, this means that academia exploits us.

The Academic System will never stop exploiting Early Career Researchers

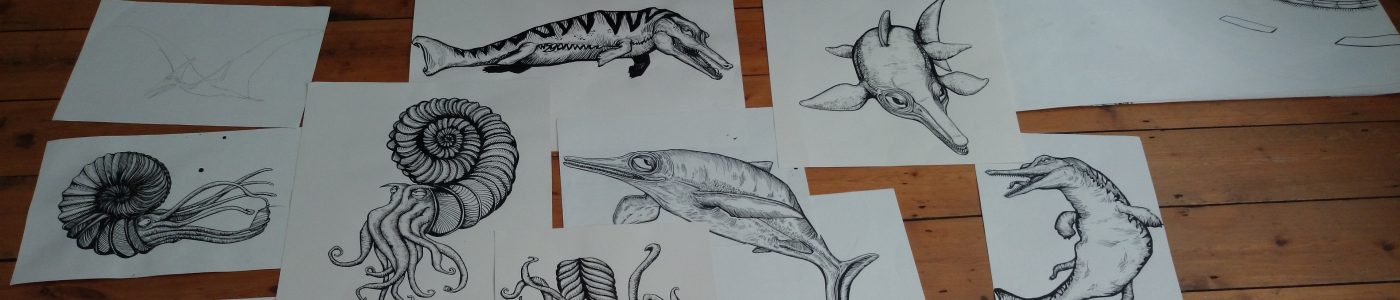

I love this career. I love discovery. I love finding new molecules or biosynthetic pathways or microbial adaptations. I love using those insights to discover something new about our Earth. And I just love reading about and discussing other people’s ideas and discoveries. And I love teaching and mentoring and supporting colleagues.

And when you love your job so much that it is a career, love your career so much that it is part of your identity, you will be exploited. The system – employers, the sector, funders – cannot help it. Even the kindest, most benevolent line managers cannot help it. As a Head of School, I do it. And it comes down to this:

In a market with limited opportunities, where success is 90% down to luck, where the competitors all have intelligence and passion, the only thing that you have any real control over is how hard you work.

You cannot change the results of your experiments, the capabilities of your instruments (within reason), the jobs available. You cannot change your gender or skin colour.

But you can volunteer to teach one more class or serve on one more committee. You can come in on the weekend to generate one more finding for one more paper. If no jobs are available you can write your own Fellowship application. And those all will help and they will give you a sense of agency in a world in which you have so little control. And it is exploitation. It is. And I don’t know how to change it.

What I will say is this: If you get the job you dreamt of, you are brilliant and lucky; and if you do not, it is because you are brilliant and unlucky. But also: that we have trained you to have limited dreams. Perhaps the academic dream is your true calling, but know that your brilliance and skills are valued and will be valued in places and by people you have yet to dream of.

The academic system will never stop exploiting you and especially your need for validation.

Almost everyone I know has imposter syndrome. It is worse in minoritised, women, working class academics. But it is widespread. We all doubt ourselves and our achievements. When we are at the start of our career, we are desperate to prove ourselves. In the middle of our career, we are anxious that our peers do not respect our achievements. At the end of our careers, we worry about losing our edge, being washed up, old news.

Imposter syndrome is an anxiety disorder that most of us face because of the conflicts between our self-doubt and ambition.

But more fundamentally, it is a direct consequence of a system that wants us to doubt ourselves and wants us to continually seek affirmation. Invited Talks, Fellowships, Prizes, High Impact Papers, Citations, H-indices. So many metrics. Most Universities literally have ‘Esteem Indicators’ as part of our Promotions criteria. And this eats at all of us. It makes us lose sleep and have anxiety disorders. It makes us check Google Scholar or bristle with envy when our friends when a prize or get a high profile paper. I’ve seen staff dangle the promise of jobs in front of ECRs and I’ve seen Fellows of esteemed societies dangle the promise of legacy and esteem. I’ve seen an FRS threaten Heads of School and Deans if they fail to comply with their requests.

This all works.

Because we have drunk the Kool Aid of exceptionalism.

And it is bullshit because so much of it is out of our control. Fellowships are ridiculously competitive, historically sexist, and still rather arbitrary (especially in who nominates us). Many of our best discoveries are accidental. Many of our most planned discoveries would have been discovered a year later by someone else but we got lucky and sorted it first. Yes, there is planning and vision and leadership. But you can labour for years, building a team, an international consortium, to tackle a critical problem and still fail to get funding. Or get the funding and just not find anything interesting.

So just like that postdoc desperate for a job, we do the one thing that is under our control. We work harder.

Longer hours. Weekends. And our institutions happily accept the generosity of our donated labour.

And it is getting worse. Universities are now financially dependent on high fee-paying overseas students, making them financially dependent on global league tables, creating a continuous pressure on performance, production, excellence, and metrics metrics metrics.

My School does well in these tables. We do not brag publicly about it, because we know that these are flawed and we won’t let our self-worth be based on them. Most of all, we refuse to treat the scientific endeavour – the collaborative quest for knowledge – as a competition. But quietly, amongst ourselves, especially on difficult days, we do allow that success to tell us ‘We’re doing something right. And that is nice.’ And even that modest acquiescence to be a ‘world-leading department’ puts a huge amount of stress on nearly every one of my colleagues. And as Head of School, no matter how much I support and reassure my staff that we are doing okay, to be kind to ourselves, that we support one another no matter what – the relief I can provide from that desperate desire to be excellent is fleeting and incremental.

Because we’ve drunk the Kool Aid. Even as I sit here, typing this, rejecting this narrative, I feel it. What papers can I push out; what grants can I be writing; what more do I have to prove. I can sit here writing that I reject this system and still feel bitter that I was not nominated for an award, recognised by some esteemed society, invited to give a talk by my colleagues.

So where does the working class academic (or racial minority or feminist) aspect come into all of this?

Because we have been programmed for this bullshit for our entire goddamned lives.

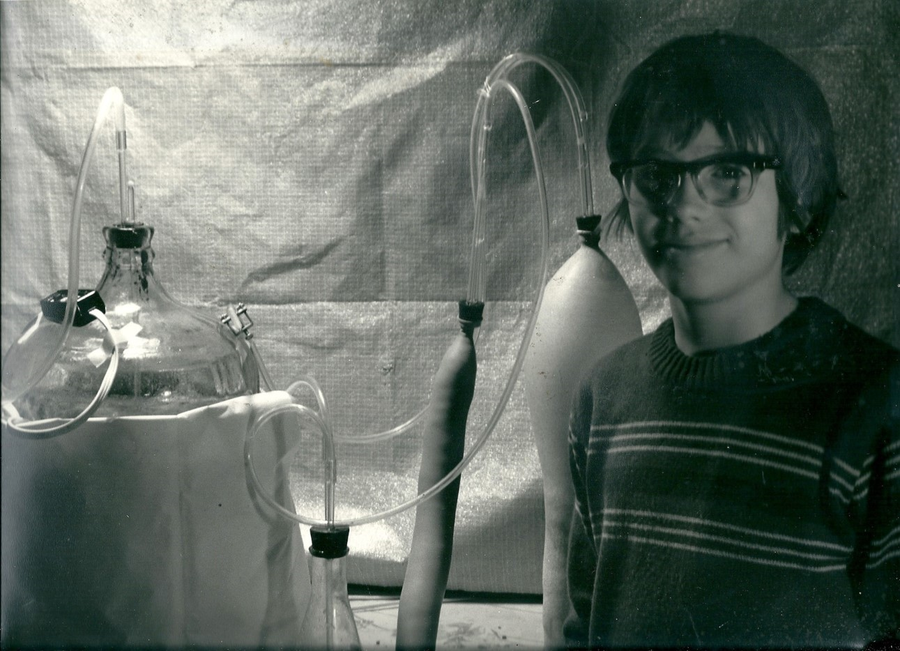

Working class kids have to put in long hours just so our families survive, creating working patterns that are then exploited by employers the rest of our lives. I worked on the farm from when I was seven, and had a part-time job from when I was 16.

But of course, social mobility says that working at that rate is just baseline. If you want to really succeed, you must work hard enough to be extraordinary. Are you doing okay? Work harder and be better than average. Are you doing well? Work harder and be the best. Be better than the best. That is how you escape poverty – be the best athlete, pianist or scholar. Win. Break records. Never stop; never rest. Or someone else will take your spot.

Fuck me, I have been living in this mindset for over 40 years.

You’ll never fit in

I’m lucky. I’m a geologist and our discipline, even in the ivory tower, rejects most pretensions. We wear shorts and t-shirts. We drink wine but also beer. We understand that on a field course, all of us had to find a tree to piss behind. I’m not sure I could have survived in a different discipline.

One of my favourite examples of this comes from my favourite Organic Geochemistry conference. I was quite anxious about attending my first one as it was a small, intimate conference. Aside from the academic anxiety of always being ‘on’, with effervescing conversations about the state of the discipline at breakfast, lunch and dinner, I was anxious about whether this working class kid could fit into the social norms. I was particularly anxious because at that time, a tradition was a wine tasting. I was a beer-drinking wine illiterate (I’m now a near-teetotal wine illiterate). But. There were so many friendly layers of subversion. The organisers were kind, patient and happy to teach. They grudgingly accepted the insurrection from those who would try to win with the cheapest off-brand wine they could find. Many opted out. Of course, in later years, it faded as we recognised that alcohol-centrism was inappropriate.

But I look at those moments of understanding and insurrection as signs of hope and change. In other contexts, I did feel like a redneck and a fool; but I gained strength knowing that these were far from universal. Being an American in the UK gave another line of protection, as my cultural ignorance was hard to pin down. Mostly, I found oases of friendships, departments, research groups and disciplines where comportment, elocution, fashion and appearance (all part of someone else’s imagined ideal of etiquette) were just not that important.

And yet… I was also told not so long ago that I would have an uphill climb to become a Fellow of the Royal Society because I lacked a ‘certain gravitas.’ What the fuck do y’all think that was referring to??

So… we never entirely fit it.

And… most of us will never again fit in at home.

Academia makes you move away from home. We have become so much more sophisticated in rejecting the narrative that postdocs must move every year or two years. Nonetheless, the numbers do not work in your favour if you want a University or research institute job near your home town. Most of us move across the country; many of us move to other countries. We move away from home, from our friends and families, from the familiar places. That is an adventure, but it comes with consequences.

Of course, if you are working class, you have not just moved far from home physically you have likely moved far, very far from your family culturally. You have different life experiences, you often adopt different politics a different world view. Often, you adopt different values.

The first summer after University, I returned home and my job as a stockboy in the local supermarket. My family and friends jokingly called me ‘College Boy.’ It wasn’t mean; it was friendly and filled with pride. Ten years later, our conversations had become reminiscing and awkward silences. Twenty years later, we fight.

I’m glad that I have changed. I am glad that I have awoken to the racism and bigotry that lurked in our conversations. I am glad that I now see the struggle of Black people and immigrants as different versions of class struggle, and I am glad that I consider this while understanding intersectionality and my own privilege.

But sometimes the disconnection that comes from moving so very far away, geographically as well as culturally and politically, is overwhelming.

Early career working class academics, I need you to understand this: At times in your lives you will feel terribly painfully alone. Not always; you will meet and love amazing people. But there will be times.

****************************

Academia isn’t special. It is a business. In a capitalist society, it exists to make money and it makes money by exploiting its work force and its customers. I am grateful that I work in an institution where my bosses are kind. But they cannot change the fundamentals of a market-driven sector. That sector exploits us. And it especially exploits our insecurities, anxiety and fear. And given how anxiety and fear are inequitably woven through society, through class and race and disability and gender, Universities exploit unfairly and with discrimination.

****************************

I’ve learned from speaking about climate change, that it is not enough to talk about problems without also talking about solutions. I’ve got no easy solutions but here are some thoughts.

In building a career, build something more than a career. Build friendships and relationships, with peers and colleagues, those in other disciplines, your partners in society. Build knowledge and wonder, learn, discover. But be careful. Those approaches can degrade work-life balance. And they can create an even greater dependency on your career. So do not spin a web that traps you but build relationships that support you and lifelines that can rescue you.

Do not work long hours or weekends. Of course, do so sometimes, when running an overnight experiment or racing to meet the occasional deadline. But do not overwork as a habit. I understand the temptation. I do. And resisting it is hard. But it will not make a difference. One more paper will not make a difference. It will not help you get a job, when luck is so important. It won’t solve your anxiety or imposter syndrome. And in all likelihood your overall productivity will be greater if you maintain a healthier balance of all aspects of your life.

What is far more valuable – and it is a quality that many working class people have in abundance – is persistence. I do not mean only the potentially toxic persistence of sticking with a career and precarious roles if the associated job uncertainty is undermining your wider life. Instead, it is the persistence to re-run experiments when they fail, to resubmit papers that are rejected, to resubmit Fellowship applications that are declined. Working class or not, academia is characterised by more rejections than successes, and our ability to take the hit, allow ourselves a finite period of justified sadness or anger, and then quickly getting right back in the game is essential. I cannot count the times my Mom either literally of figuratively made be get back on that horse. You can resubmit that rejected paper in a few days or a month or it can simmer on your laptop for three years, causing anxiety whenever you think about it. (As a corollary and to *everyone else in academia* – be fucking kind in those rejections. We are asking people to be persistent not resilient in the face of our toxicity.)

If you are going to work those extra hours, however, then damn it, put that extra labour into what you love, what you want to. If the system is exploitative, at least the academic system is one in which you have some modicum of control over how you will be exploited. If your desperation forces you to work weekends, work less on productivity, less on one more publication, but instead read a paper, discover or share something new, find or share some wonder in this collective endeavour of knowledge. It is giving in to the system, but it is also owning your agency.

To do this, you need to find the means to make decisions based on your values, not the values of everyone and everything that surrounds you.

You must quiet that noise and discover what it is about your career that is really really important to you. And you must not confuse that with what you have been taught is important, what societies and awards say is important, what appears important to your friends and colleagues and peers. What academia is continuously telling you has value and what does not. If you know yourself, use that to dismiss all of the extraneous bullshit and centre what you value and enjoy; and then use that to prioritise your efforts, empower your decisions. And do that at every single stage of your life.

And… seek help in navigating those decisions. I’ve never had counselling despite guiding so many friends, colleagues and students in that direction. I need to have some. I should have had some in college, when I had anger issues, when I self-harmed through sports and fights. I should have had some as a working class academic, whose marriage collapsed, who put my great capacity for love and compassion into projects rather than friendships. I should have some now as a Head of School, dealing with multiple crises in our sector, distraught students, stressed staff and frustrations at an unfair world and incompetent leadership. Writing this blog is a poor substitute for that.

But I never had the money, and when I had the money I “never had time”. And talking to counselors is just not what we do, not us working class farm kids from Ohio. So I’ll make you a deal. I will find the time and reject my deeply ingrained biases to ask for help. If you promise to do the same.

And finally: I love academia. It is a great career, filled with intellectual flexibility, creativity, collaboration and the joy of discovery. These blogs are not meant to say otherwise; rather, they are a corrective to the myth that academia is an ideal career, based solely on merit and without flaw. We can hold simultaneous truths, loving something while wanting it to improve. Along those lines, I once promised a PhD student that I would never offer them advice about how to navigate a flawed and exploitative system, without also committing to change it. And I do commit to changing this, to minimising exploitation and creating more oases where those who do not fit the typical academic profile can find homes. And ultimately, I commit to destroying the very idea of a typical academic. And together, we can commit to revolution and real fundamental change.