My Dad died three weeks ago.

I am not comfortable about sharing this. I share a lot in this blog and hold little back about my beliefs and politics, but I hide more than it seems. I always have.

But Covid prevented me from saying goodbye to Dad. It is preventing me from going home. It is preventing our family from mourning him together. I miss all of them. So I wanted to write some thoughts down, to put them somewhere they will not be alone and where they will wait until I can say them out loud.

I miss him so much. I remember riding around the country roads and farm fields with him; he had made these small metal-framed chairs for my brother and me and welded them onto the side of the tractor wheel basins. I remember him telling me last year, on the porch swing, to look after Mom the way Mom had looked after him. I remember him trying to understand my concerns about a foster girl we wanted to adopt – concerns I could not articulate as a 10-year old. I remember him picking me and my girlfriend up and driving us home after I had totaled the family car. I remember him taking me to college exams and interviews, and picking me up after School. I remember the way he bantered with every waitress, every check-out worker, sometimes crossing the line but never indifferent to anyone, ever. I remember him holding my hand and telling me that Shelli had died.

Dad and I disagreed on a lot of things. Most things politically. Many things that I value. But Dad (and Mom) also taught me my values and my strengths; they helped me become who I am.

Probably the most important thing he taught me was ‘Do not put up with anyone’s bullshit.’ In 1976, he decided that he had enough of working for someone else, at the local factory. So he quit to work for himself. Our family – the four of us – started a dairy farm. There is a lot that I could write about working on the farm: carrying the pails back and forth as he milked the cows; stacking hay in the loft, straw slivers sticking to your skin or in your arm, temperatures near the loft ceiling shooting past 100F, wasps buzzing around your head; his shovel scraping my hands in the freezing cold as we filled burlap bags with corn to be taken to the mill; riding in the back of the pick-up truck on the way back from town, soft-serve ice cream whipping away from me in the wind.

I loved parts of it and hated others. I loved the smells – of fresh-cut hay and fresh-ground corn – and I hated the rattling, abrasive noise of the farm equipment. I loved being with my family nearly every day; even when I claimed that I did not. But it was not an easy life and it was not a lucrative life – and although that was frustrating, we did not care most days. Because we worked for ourselves – and although we had to answer the diurnal demands of the cows, the demands of mortgages and loans, the demands of floods and drought, we did not answer to a boss.

Dad, Mom, my brother and I all took different lessons from that life – we all recognised that you could never escape other people’s ‘bullshit’ entirely. Banks replaced bosses. Dad ultimately embraced a libertarian view while I adopted a socialist one. And so even though we differed in our beliefs, they sprung from the same outrage against perceived unfairness and stupidity.

*************

But choices have consequences. And one of the main consequences of being a rural Ohio dairy farmer was being poor. Rural poverty, especially when you are a farmer, is an unusual thing. We had land to run about in, room to roam and play; my brother and I hunted frogs and salamanders in our creek, fished in local ponds, and built dams and forts. We always had food in the freezer or the cellar, beef from the farm and vegetables from the garden. We did not feel poor in many ways. But we did not have money. We often did not have new clothes, except as hand-me-downs or ill-fitting gifts. We did not have the cool toys. For a while, we did not have hot water. Some dental appointments were cancelled. Bills and uncertain weather and farm accidents loomed over us – and occasionally crashed into our lives and reminded us how precarious and precious they were.

But we had ambition and dreams; and Mom and Dad never let their own plans inhibit those of my Brother and me.

They supported us in every possible way. There seemed to be a contract between them, that no matter what choices they made, we would have every opportunity in the world.

I always loved science. I had a little blue travel suitcase that was packed full of my science books, mostly astronomy and planetary science, that I took everywhere. The 1980 version of the Larousse Guide to Astronomy was read to tatters. Somehow Mom found me the National Geographic issues associated with the Voyager expeditions and they got me a subscription to Astronomy magazine long before I could understand most of the articles.

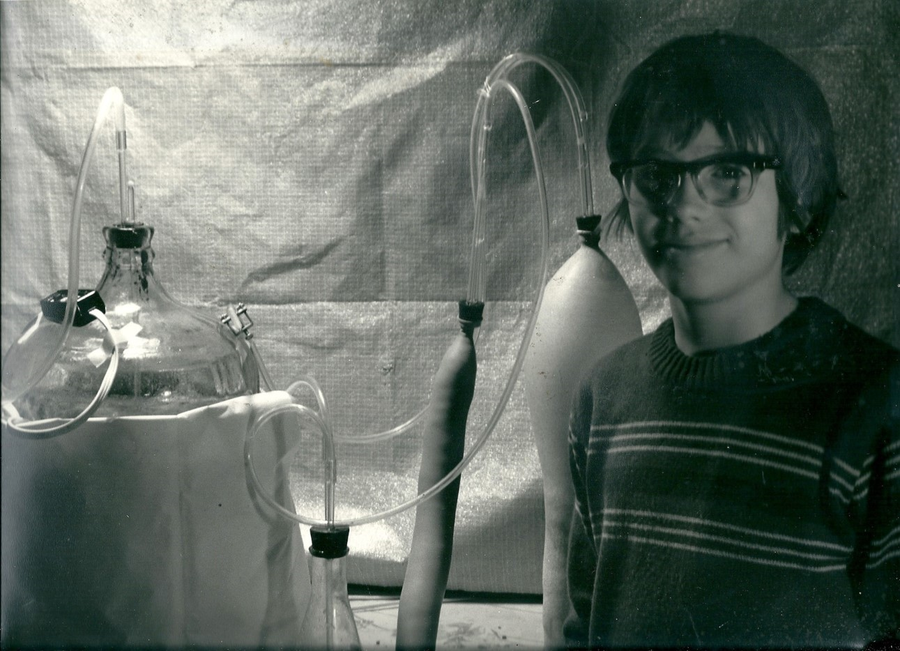

But Dad was the first person who helped me how to do science, how to do an experiment. In 7th grade, as I prepared for the Science Fair, he suggested that I think about some recent work on incubating cow manure as a source of energy for rural communities. That’s right – my Dad introduced me to methanogenesis, biogeochemistry and renewable energy… in 1983. He helped me think about how we might test it, and he took me to the Chemistry Department of the local Hiram College to borrow the lab glassware we would need. He always had a knack for rigging things together, and he helped me connect the tubes and balloon reservoirs to our vat of heated manure and a valve that allowed us to burn the methane as evidence of its production. I won 3rd place in the county Science Fair for the project: Methane From Manure – Is it for You?

Dad shares the prize, but shares no blame for the title.

I got good grades throughout School – College was always on the cards. Mom had to push me pretty hard in elementary School, but by the time of Middle School I had developed a rather strong internalised sense of ambition; my parents nurtured and supported that. In particular, they supported my desire to attend a private and elite High School, which we had been led to believe was key to getting into a top college. The School recruited us and wooed us; and when I got admitted, they told us that there was no prospect for financial aid. I was crushed. So instead, Dad fought for me to have a fast-track High School experience, to compensate for this setback by graduating from High School a year early. Ultimately, I opted for the experience of the full four years of High School and I sure as hell do not regret missing out on the private High School. But I remember my Dad arguing with admissions directors and guidance counselors on my behalf, fighting for his son to have every opportunity.

I think my strongest memories are of him driving me to Forensics tournaments nearly every Saturday morning for four years, all though the winter, in every weather, weekend after weekend, and already after he had milked the herd. My parents had a simple rule for my brother and me when it came to extracurricular activity: they did not care what we did – sports, band, choir, debate, science clubs – but we had to do something. I think they viewed it as essential for our character, to do something real, something neither from the farm nor from the classroom.

I joined the Forensics (Speech) Team. And I was good at it, making it the State championships a few times. The tournaments were every Saturday during the School year and all over NorthEast Ohio. After milking the cows, Dad would drive me to the High School by 8am, so I could catch the Team school bus to wherever the tournament was being hosted. Through the winter dark, he always drove me. And through god knows how many blizzards – lake effect blizzards – at those early hours before the snow plows and salt trucks had emerged.

I remember one morning when the snow had fallen so hard, I was sure he would say we could not go. He did not, and like every other Saturday we headed off at 7:30 am, him fresh from the barn and me wearing my suit. The roads were treacherous with compacted snow. And as we carefully inched down State Route 82 towards Derthick’s Hill, a not unimpressive hill for NE Ohio and so-named because of the owners of the farm at its summit, we saw red lights twisting and turning towards us, the brake lights of cars sliding, out of control down the impassable hill. Some into ditches and some towards us. He turned to me and asked, ‘How important is this tournament?’ And I said that it was really important. And so he turned down a snow-packed country side road and drove the back way, over uneven and twisting ice-packed gravel and dirt roads and through blizzard-occluded views, until we finally reached the High School and the waiting bus.

I don’t remember a thing about that tournament; all I remember is that my Dad got me there.

Not all memories are good. They never can be; nor should they be. And failing to remember the disagreements or the really tough financial times makes a lie out of remembering the many good times. But I can honestly say that not once in my life have I ever doubted that my parents had my best interests at heart, that even when they did not entirely understand my dreams or decisions, they supported them. They loved the family life we shared on the farm, but we all understood that would end after I started College and my brother followed two years later. They never thought I would move so far, across an Ocean, but they did know I would move away.

These were different choices than they had made. My Dad joined the Army out of School instead of college. But I never would have gone to college nor completed it without him. I never would have gotten my PhD. I dedicated my PhD to both Mom and Dad and gave Dad the only copy of my Thesis I ever printed, which remains unbound in his closet.

Years later, I found myself in a submersible exploring the mud volcanoes and brine lakes of the Mediterranean seafloor, searching for methane seeps and the organisms associated with them. I was so far away from the farm and yet so close; we were exploring the landscape like my brother and I had explored the forgotten corners of our farm, and we were looking for some of the same organisms that I had studied with my Dad in that 7th grade Science Project.

Then and now, I think of Dad and am grateful to him. For the sacrifices he made, the lessons he taught me and the opportunities he gave me. I love him and I miss him. But he has always been with me and he always will be.

Rich-

I am sorry for your loss- I did not know he passed.

I knew your dad. He was a good man. I knew you disagreed..but I also could see how much love and pride he had for you and your family. He always remembered me, said hello, and had a smile or hand to offer if needed. I liked your dad-remember there is not an expiration on grief and memories of him should comfort you as you move forward in life. Let me know if there is anything I can help in any way. Hugs

gwen

I, too, am sorry for your loss, Rich. This was a wonderful tribute to your dad, and I read with interest about your speech team experience. You showed in this piece that we CAN get along, even if we disagree politically. Again, my condolences. Snook

I’m so sorry for your loss. Another friend lost her dad last month and couldn’t be with him to say goodbye. As I think back to when my dad died, 9+ years ago, when I rushed across the ocean and was able to hold his hand and talk to him, I think this pandemic is the cruelest to the dying and their close ones. I hope you can come to peace with it

Hello Rich, I am sorry of your loss of your Dad. Your parents gave you good values and a vision that has improved the lives of many, when you and your team were recognised as Earth Champions

We send you our best wishes and hope

you do have a chance to return to see your Family again in the US, when this virus passes.

with kindest wishes,

Fiona Mathews,