Recently, our group published a paper about the environmental conditions of the Zechstein Sea, which reached from Britain to Poland 270 million years ago. Our paper revealed that for tens of thousands of years, some parts – but only parts – of the Zechstein Sea were anoxic (devoid of oxygen). As such, it contributes to a vast body of research, spanning the past 40 years and representing the efforts of hundreds of scientists, which has collectively transformed our understanding of ancient oceans – and by extension future ones.

The types of processes that bring about anoxia are relatively well understood. Oxygen is consumed by animals and bacteria as they digest organic matter and convert it into energy. In areas where a great deal of organic matter has been produced and/or where the water circulation is stagnant such that the consumed oxygen cannot be rapidly replenished, concentrations can become very low. In severe cases, all oxygen can be consumed rendering the waters anoxic and inhospitable to animal life. This happens today in isolated fjords and basins, like the Black Sea. And it has happened throughout Earth history, allowing vast amounts of organic matter to escape degradation, yielding the fossil fuel deposits on which our economy is based, and changing the Earth’s climate by sequestering what had once been carbon dioxide in the atmosphere into organic carbon buried in sediments.

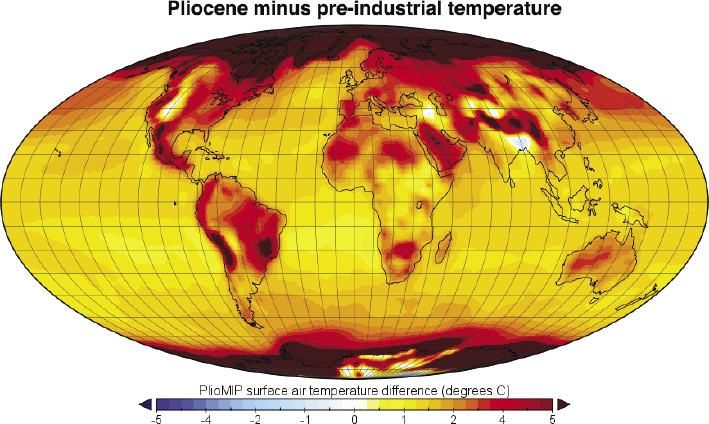

|

| Red circles show the location and size of many dead zones. Black dots show Ocean dead zones of unknown size. Image source: Wikimedia Commons/NASA Earth Observatory |

In some cases, this anoxia appears to have been widespread; for example, during several transient Cretaceous events, anoxia spanned much of what is now the Atlantic Ocean or maybe even almost all of the ancient oceans. These specific intervals were first identified and named oceanic anoxic events in landmark work by Seymour Schlanger and Hugh Jenkyns. In the 1970s, during the earliest days of the international Deep Sea Drilling Program (now the International Ocean Discovery Program, arguably the longest-running internationally coordinated scientific endeavor), they were the first to show that organic matter-rich deep sea deposits were the same age as similar deposits in the mountains of Italy. Given the importance of these deposits for our economy and our understanding of Earth and life history, scientists have studied them persistently over the past four decades, mapping them across the planet and interrogating them with all of our geochemical and palaeontological resources.

In my own work, I have used the by-products of certain bacterial pigments to interrogate the extent of that anoxia. The organisms are green sulfur bacteria (GSB), which require both sunlight and the chemical energy of hydrogen sulfide in order to conduct a rather exotic form of bacterial photosynthesis; crucially, hydrogen sulfide is only formed in the ocean from sulfate after the depletion of oxygen (because the latter yields much more energy when used to consume organic matter). Therefore, GSB can only live in a unique niche, where oxygen poor conditions have extended into the photic zone, the realm of light penetration at the very top of the oceans, typically only the upper 100 m. However, GSB still must compete for light with algae that live in even shallower and oxygen-rich waters, requiring the biosynthesis of light harvesting pigments distinct from those of plants, the carotenoids isorenieratene, chlorobactene and okenone. For the organism, this is an elegant modification of a molecular template to a specific ecological need. For the geochemist, this is an astonishingly fortuitous and useful synthesis of adaptation and environment – the pigments and their degradation products can be found in ancient rocks, serving as molecular fossil evidence for the presence of these exotic and diagnostic organisms.

And these compounds are common in the black shales that formed during oceanic anoxic events. And in particular, during the OAE that occurred 90 million years ago, OAE2, they are among the most abundant marker compounds in sediments found throughout the Atlantic Ocean and the Tethyan Ocean, what is now the Mediterranean Sea. It appears that during some of these events anoxia extended from the seafloor almost all the way to the ocean’s surface.

********

Today, the deep sea is a dark and empty world. It is a world of animals and Bacteria and Archaea – and relatively few of those. Unlike almost every other ecosystem on our planet, it is bereft of light and therefore bereft of plants. The animals of the deep sea are still almost entirely dependent on photosynthetic energy, but it is energy generated kilometres above in the thin photic zone. Beneath this, both animals and bacteria largely live off the scraps of organic matter energy that somehow escape the vibrant recycling of the surface world and sink to the twilight realm below. In this energy-starved world, the animals live solitary lives in emptiness, darkness and mystery. Exploring the deep sea via submersible is a humbling and quiet experience. The seafloor rolls on and on and on, with only the occasional shell or amphipod or small fish providing any evidence for life.

|

| “Krill swarm” by Jamie Hall – NOAA. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons |

And yet life is there. Vast communities of krill thrive on the slowly sinking marine snow, can appear. Sperm whales dive deep into the ocean to consume the krill and emerge with the scars of fierce battles with giant squid. And when one of those great creatures dies and its carcass plummets to the seafloor, within hours it is set upon by sharks and fish, ravenous and emerging from the darkness for the unexpected feast. Within days the carcass is stripped to the bones but even then new colonizing animals arrive and thrive. Relying on bacteria that slowly tap the more recalcitrant organic matter that is locked away in the whale’s bones, massive colonies of tube worms spring to life, spawn and eventually die.

But all of these animals, the fish, whales, tube worms and amphipods, depend on oxygen. And the oceans have been like this for almost all of Earth history, since the advent of multicellular life nearly a billion years ago.

This oxygen-replete ocean is an incredible contrast to the north Atlantic Ocean during at least some of these anoxic events. Then, plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs and mosasaurs, feeding on magnificent ammonites, would have been confined to the sunlit realm, their maximum depth of descent marked by a layer of surprisingly pink and then green water, pigmented by the sulfide consuming bacteria. And below it, not a realm of animals but a realm only of Bacteria and Archaea, single-celled organisms that can live in the absence of oxygen, a transient revival of the primeval marine ecosystems that existed for billions of years before more complex life evolved.

We have found evidence for these types of conditions during numerous events in Earth history, often associated with major extinctions, including the largest mass extinction in Earth history – the Permo-Triassic Boundary 252 million years ago. Stripping the ocean of oxygen and perhaps even pumping toxic hydrogen sulfide gas into the atmosphere is unsurprisingly associated with devastating biological change. It is alarming to realise that under the right conditions our own oceans could experience this same dramatic change. Aside from its impact on marine life, it would be devastating for us, so dependent are we on the oceans for our food.

The conventional wisdom has been that such extreme anoxia in the future is unlikely, that Cretaceous anoxia was a consequence of a markedly different geography. North America was closer to Europe and South America only completely rifted from Africa about 150 million years ago; the ancient Atlantic Ocean was smaller and more restricted, lending itself to these extreme conditions.

And yet questions remain. What was their trigger? Was it really a happenstance of geography? Or was it due to environmental perturbations? And how extensive were they? The geological record preserves only snapshots, limiting the geographical window into ancient oceans, and this is a window that narrows as we push further back in time. In one of our recent papers, we could not simulate such severe anoxia in the Atlantic Ocean without also simulating anoxia throughout the world’s oceans, a truly global oceanic anoxic event. However, that model can only constrain some aspects of ocean circulation and there are likely alternative mechanisms that confine anoxia to certain areas.

************

Over the past twenty years, these questions have intersected one another and been examined again and again via new models, new geochemical tools and new ideas. And an emerging idea is that the geography of the Mesozoic oceans was not as important as we have thought.

That classical model is that ancient oceans, through a combination of the aforementioned restricted geography and overall high temperatures, were inherently prone to anoxia. In an isolated Atlantic Ocean, oxygen replenishment of the deep waters would have been much slower. This would have been exaggerated by the higher temperatures of the Cretaceous, such that oxygen solubility was lower (i.e. for a given amount of oxygen in the atmosphere, less dissolves into seawater) and ocean circulation was more sluggish. Consequently, these OAEs could have been somewhat analogous to the modern Black Sea. The Black Sea is a restricted basin with a stratified water column, formed by low density fresh water derived from the surrounding rivers sitting stably above salty and dense marine deep water. The freshwater lid prevents mixing and prevents oxygen from penetrating into deeper waters. Concurrently, nutrients from the surrounding rivers keep algal production high, ensuring a constant supply of sinking organic matter, delicious food for microbes to consume using the last vestiges of oxygen. The ancient oceans of OAEs were not exactly the same but perhaps similar processes were operating. Crucially, the configuration of ancient continents in which major basins were isolated from one another, suggests a parallel between the Black Sea and the ancient North Atlantic Ocean.

But over the past twenty years, that model has proved less and less satisfactory. First, it does not provide a mechanism for the limited temporal occurrence of the OAEs. If driven solely by the shape of our oceans and the location of our continents, why were the oceans not anoxic as the norm rather than only during these events? Second, putative OAEs, such as that at the Permo-Triassic Boundary occur at times when the oceans do not appear to have been restricted. Third, coupled ocean-atmosphere models indicate that although ocean circulation was slower under these warmer conditions, it did not stop.

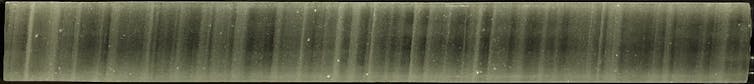

But also, as we have looked more and more closely at those small windows into the past, we have learned that during some of these events anoxia was more restricted to coastal settings. And that brings us back to the Zechstein Sea. We mapped the extent of anoxia at an unprecedented scale in cores drilled by the Polish Geological Survey, and we discovered an increasing abundance of GSB molecular fossils in rocks extending from the carbonate platform and down the continental slope, suggesting that anoxia had extended out into the wider sea. But when we reached the deep central part of the basin, the fossils were absent. In fact, the sediments contained the fossils of benthic foraminifera, oxygen dependent organisms living at the seafloor, and the sediments had been bioturbated, churned by ancient animals. The green sulfur bacteria and the anoxia were confined to the edge of the basin, completely unlike the Black Sea. This is not the first such observation and this is consistent with new arguments mandating not only a different schematic but also a different trigger. And perhaps that trigger was from outside of the oceans.

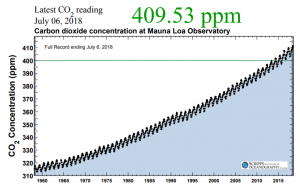

If the trigger was not solely a restriction of oxygen supply then the alternative is that it was an excess of organic matter, the degradation of which consumed the limited oxygen. A likely source of that organic matter and one that is consistent with restriction of anoxia to ocean margins is a dramatic increase in nutrients that stimulated algal blooms – much like what is occurring today. And that increase in nutrients, as elegantly summarized by Hugh Jenkyns, could have been caused by an increase in erosion and chemical weathering, driven by higher carbon dioxide concentrations, global warming and/or changes in the hydrological cycle, all of which we now know occurred prior to several OAEs. And again, similar to what is occurring today.

It is likely that today’s coastal dead zones are due not to climate change but to how we use our land and especially to our excess and indiscriminate use of fertilisers, most of which does not help crops grow or enhance our soil quality but is instead washed away to pollute our rivers and coastal seas. And yet that only underscores the lessons of the past. They suggest that global warming might exacerbate the impacts of our poor land management, adding yet another pressure to an already stressed ecosystem.

The Zechstein Sea study is not the key to this new paradigm (and that ‘paradigm’ is far from settled). There is probably no single study that marked our change in understanding. Instead, this new model has been gradually emerging over nearly 20 years, as long as I have been studying these events. New geochemical data, such as the distribution of nutrient elements, suggest that many of these anoxic episodes, whether local or global, were associated with algal blooms. And other geochemical tools, such as the isotopic composition of trace metals, provide direct evidence for changes in the chemical weathering that liberated the bloom-fueling nutrients.

Science can move in monumental leaps forward but more typically it evolves in small steps. Sometimes, after years of small steps, your understanding has fundamentally changed. And sometimes that change means that your perception of the world, the world you love and on which you depend, has also changed. You realize that it is more dynamic than you thought – as is its vulnerability to human behaviour.

——————————