Y’all! A blog adapted from my 19 July 2019, 50th anniversary twitter thread about the Apoll0 11 #Apollo50th lunar samples and the search for life. Adapted from a presentation by @ogu_bristol founder Geoff Eglinton, who led the search for biomolecules. The team included him, James Maxwell, Colin Pillinger, John Hayes and others, titans of the organic geochemistry field. University of Bristol press release here: (bristol.ac.uk/news/2019/july…)

Today, the @ogu_bristol studies archaeology, past climate, the Earth system, environmental pollution, astrobiology and the evolution of life. We are all proud to build on the legacy of Geoff and James, shared between @UoBEarthScience and @BristolChem (bristol.ac.uk/chemistry/rese…)

Geoff’s involvement dated back to 1967 when @NASA first commissioned proposals for analyses of the rocks! (Geoff – like all of us – also smelled an opportunity for investment in fantastic new kit!)

This was exciting news in Bristol – but the @bristollive (Bristol Post) headline rather captured the gender stereotypes of the day. As we know, there were many hidden figures at NASA. And although the OGU was mostly men in 1969, women were a critcal part of the group.

“We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do these other things, not because they are easy but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills’ JFK, 1962. A thrilling statement of scientific intent.

Everyone had their own role to play in the post-mission effort do derive as much scientific value as possible from this great human endeavour. This is Geoff’s list of the ‘Big Questions’:

Images of the launch…

… and some of Geoff’s favourite images from the mission. All courtesy of @NASA

The Rocks Arriving at NASA! They had to be quarantined for three weeks in the Lunar Receiving Lab to ensure they were not contaminated with extraterrestrial life, radiation, toxins.

And then processed via different labs for different analyses, partitioning, etc. This flow chart looks SO simple, given what we have all personally experienced in distributing far less precious samples!

Love these photos.

This discussion over how to process some of the most valuable samples in the history of humanity just looks too damn chill. I’ve seen scientists nearly come to blows over how to partition a marine sediment core!

Bristol newspapers took this seriously: “The Four Just Men of Bristol.” The rocks arrived in Bristol on 23 Oct 1969, an event that we celebrated with a talk by James Maxwell and a fantastic introduction by Colin Pillinger’s wife, Judy.

Sidebar: (John Hayes was Kate Freeman’s PhD supervisor; and she was mine. The legacy of this mission and the analytical techniques that spun out of it is vast. And now I co-lead this same group. This is humbling.)

This is James Maxwell and Colin Pillinger transferring the moon dust. I never had the privilege of working with Colin, but James, Geoff and John are titans in the field from whom I had the privilege to learn.

This is it. This is what we got.

The most precious samples in the history of humanity. Looking for trace quantities. That could change how we perceived our place in the cosmos. No pressure.

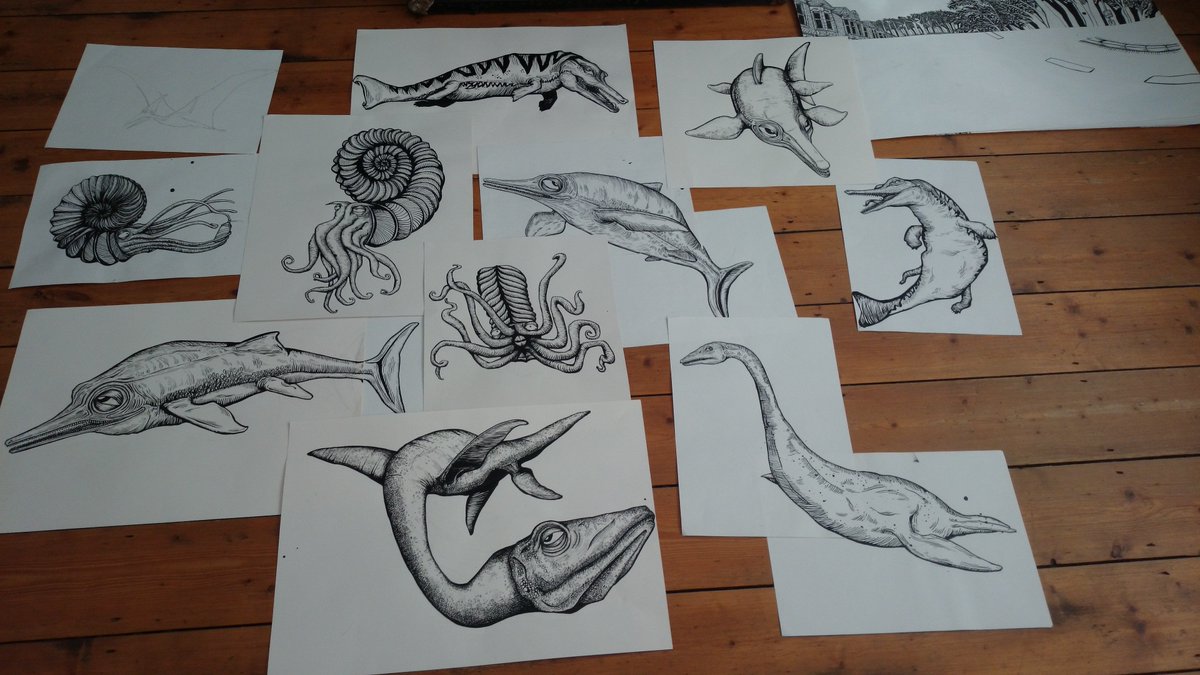

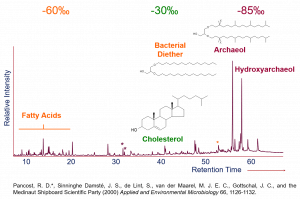

What. Did. They. Find?? The @ogu_bristol had two scientific goals. The first, as we are organic geochemists), was looking for molecular evidence for life.

And?

They found none. Despite at least some pop culture suggestions to the contrary!

Including our own Bristol pop culture, right @aardman?

One of my fondest memories of Geoff was Richard Evershed asking him at the end of the seminar ‘Did you expect to find any evidence?’

Geoff: ‘Ha ha ha ha… No.”

But they did make fascinating discoveries! They found traces of methane embedded in the lunar soil. This important organic compound could be formed in minerals by solar wind bombardment of the surface with carbon & hydrogen. But lunar surface is also bombarded by micrometeorites

So which was the correct mechanism? Geoff’s explanation in his own words/slides and drawings!

And the inevitable @nature paper! (It turns out that it is more complicated than that. It is partially contamination and partially carbon chemistry on the lunar surface)

The adventure did not end there. They continued analysing samples from not only the Apollo missions but also the Soviet Luna missions.

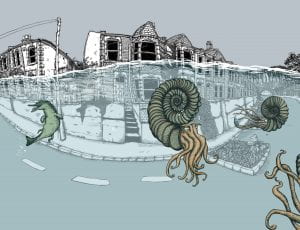

Colin Pillinger went on to pioneer UK space science for the next three decades. And the scientists and methods thrived as the foundation for a multitude of disciplines here on Earth, from chemical archaeology to climate reconstruction to tracing pollution in the environment. And the legacy thrives through over 1000 scientists – undergraduates, PhD students, post-docs, visitors, and users of the Bristol node of @isotopesUK.

Many debate the cost and priority of space science and exploration, compared to tackling real world problems. That might seem especially true now as we grapple with the immediate challenge of Covid-19 and the long-term challenge of climate change. And I agree with that, especially when exploration becomes a vanity project rather than a shared and collective intellectual endeavour. But when done right, it brings out our very best, with inevitable and profound benefits for all of society. It ensures we retain our ambitions. It ensures we remember what we can achieve together. And it creates a legacy of knowledge, innovation and scholars #Apollo50th