This was my first ever blog, inspired by Amanda W00dman-Hardy upon my appointment as Director of the Cabot Institute. It foreshadows a lot of themes to come, including how my life on a farm and research on climate change across multiple timescales informed my views on uncertainty. Many of these ideas would be refined during the Bristol Green Capital, as we co-created Bristol’s Resilience Strategy and One City Plan and collaborated with colleagues at the University of Bristol and across the city.

Improved decision making in the face of environmental uncertainty is at the heart of the Cabot Institute. Although individuals, businesses and society aspire to make logical decisions, informed by evidence and wisdom, we are also influenced by a complex mixture of emotions, ethics, political opportunism and personal beliefs. These murky waters become even more challenging to navigate when dealing with the inherent uncertainty in the basic evidence. And it becomes almost impossible when pre-conceived beliefs and opinions replace evidence. In such scenarios, uncertainty can be manipulated as a tool to undermine evidence and justify flawed decisions. This is the particular challenge of decision making in the context of complex environmental, economic and ecological issues.

To a scientist confronted with evidence that human activity is changing our environment at unprecedented rates, it is apparent that environmental uncertainty is rarely appropriately deployed in policy making. Most perniciously, it is commonly argued that the risk of an action (i.e. loss of biodiversity or increasing CO2 emissions) could be at the low end of the probability distribution – ‘the temperature might not warm that much’, ‘we might not get more hurricanes’. That is not proper governance; that is hiding behind uncertainty and hoping for the best. Nor is it appropriate to govern based on the worst-case scenario. But nor can we govern by solely considering the most likely outcome. We must recognise the range of possibilities and plan within it – strategically, flexibly, resiliently. In other words, the uncertainty brought about by ongoing environmental change is itself a profound cause for concern and a challenge for governance.

However, environmental uncertainty is not an opaque label for things ‘we do not understand’ and by an extension it is not a cause for inaction.

I grew up on a farm in the US Midwest and so environmental uncertainty to me mainly concerns our food and the people who provide it. Anyone who has ever been involved in farming understands how uncertain our environment can be. And they understand how undermining and economically challenging that uncertainty is, especially with respect to the weather (weather is not the same as climate, but it makes for a useful environmental analogy).

We had about 30 head of cattle on our small Ohio dairy farm, and my brother, parents and I needed to put aside 4000 bales of hay every summer. I loved that job – I remember the smell of drying hay and the fat bumble bees buzzing in the clover. I remember being with my family, the satisfaction of completed work and the closeness that came from achieving things together. But it was hard and uncertain work, my father cutting the grass, raking it and baling it, quickly over successive hot days so that it would dry before a summer rain shower could strip away the nutrients. Or worse: before an extended few days of rain saturated the mowed hay on the ground, causing it to become fungus-ridden and rotting it away in the field. We could work with a prediction of rain and we could work with a prediction of no rain or even drought. But we could not work with an overly uncertain prediction. Even worse were wrong (i.e. overly certain) predictions. We navigated the probabilistic terrain of the daily weather forecasts somewhat by instinct, but the stakes were high, and just three or four bad decisions in a summer would have been financially catastrophic. The farm is long gone but my Mom is still addicted to the weather reports.

But uncertainty does not mean paralysis; it means risk management. We mitigated the risk of wasted crop by renting and working fields that could yield 4500 bales rather than 4000. And those 4000 bales of hay were themselves, risk management, exceeding our likely needs. Gathering the bales and storing them in our barn’s loft was hard, sticky, hot and gritty work. The hay was delivered to the loft by a metal elevator – metal plates carried by metal chains up a metal chute, all powered by our forty-year old International Harvester tractor’s power take-off shaft. I loved doing this work on the farm – its physicality and the stimulus of all of your senses – but I do not miss that tremendous rattling, clanging noise! The loft itself could reach temperatures of 110°F and was filled with clouds of dust and darting, irritated wasps. Our necks would burn and our forearms would be filled with tiny splinters of hay.

We worked hard and put away 4000 bales each summer even though we would probably only need 3500, because we had to err on the side of caution in case there was an early winter. Or a long winter.

That is environmental uncertainty – and risk management – to me. Cutting the hay when the forecast predicts a 35% chance of rain and watching 400 bales of alfalfa rot in the field. Renting more land than we would likely need. Working 20% harder than necessary – just in case.

All of us understand this, whether it be maintaining the garden, managing the allotment or planning a holiday. This is part of human history: sound, profitable, secure decision-making has always required a confrontation with environmental uncertainty; consequently, almost all societies have strived to mitigate risks by understanding the environment, managing essential resources, and building up our own resilience.

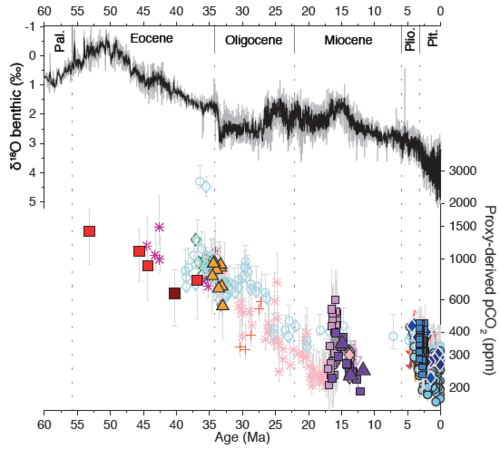

What is disturbing and unique about the 21st century is that we are no longing mitigating environmental uncertainty but instead, we are very rapidly increasing it. We are changing our planet and where and how we live upon it. Increasing carbon dioxide emissions might warm the planet by 1.5°C. Or 3°C. Or 5°C. Such warming will probably cause the Southwest of England to have wetter summers and the great food-supplying regions of the American Midwest to become drier. But there is a probability that the opposite will happen. How does the small farmer plan? For that matter, how does the huge international agritech firm plan? I would argue that the greatest challenge posed by our changing environment is not how much the Earth warms but the uncertainty in how much it will warm and the uncertainty associated with the consequences of that warming. Planning for our future – perhaps for the first time in human history – is actually becoming more uncertain every year.

But we are also learning much more about ourselves and our environment, and this perhaps makes the future a bit more certain than it might otherwise be. Currently the MET Office is improving our prediction tools and tailoring specific advice to farmers; engineers are learning how we might mitigate or even adapt to this uncertainty; and we are developing methods to limit our dependence on fossil fuel and thus the associated climate change. And we are learning how to make sound decisions in the face of it. To achieve these objectives, the Cabot Institute and similar entities are bringing together a wide variety of scientists, social scientists, managers and engineers, all of whom share expertise with the community and industry. That expertise includes those who deal specifically with quantifying uncertainty, the underlying psychology and sociology of decision making, and the clash of ethical and pragmatic ideas that inform policy making. The world’s population is growing and with it our basic food, water and energy needs; to provide for those needs, we must make our future more certain but also more resilient and adaptable.