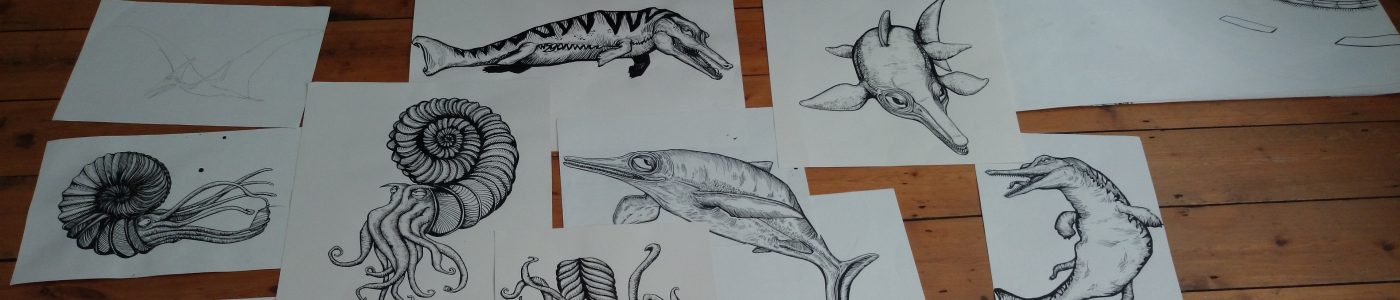

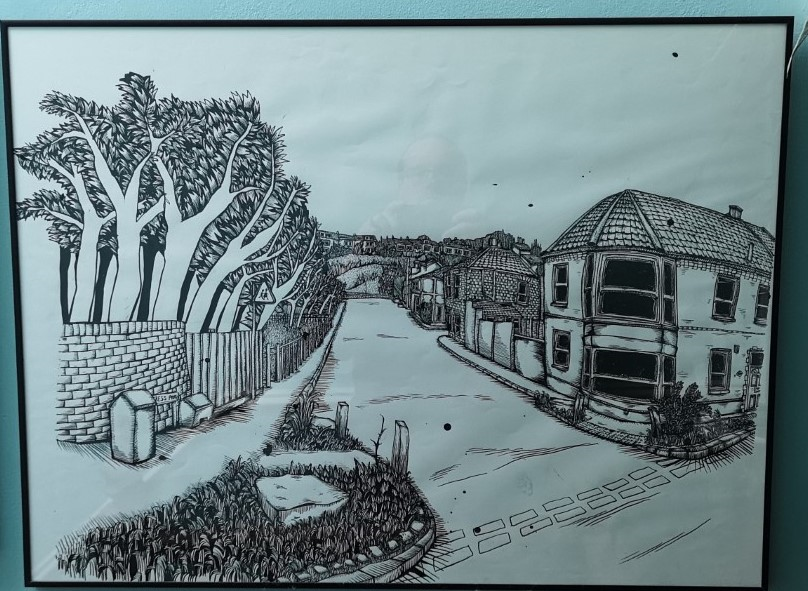

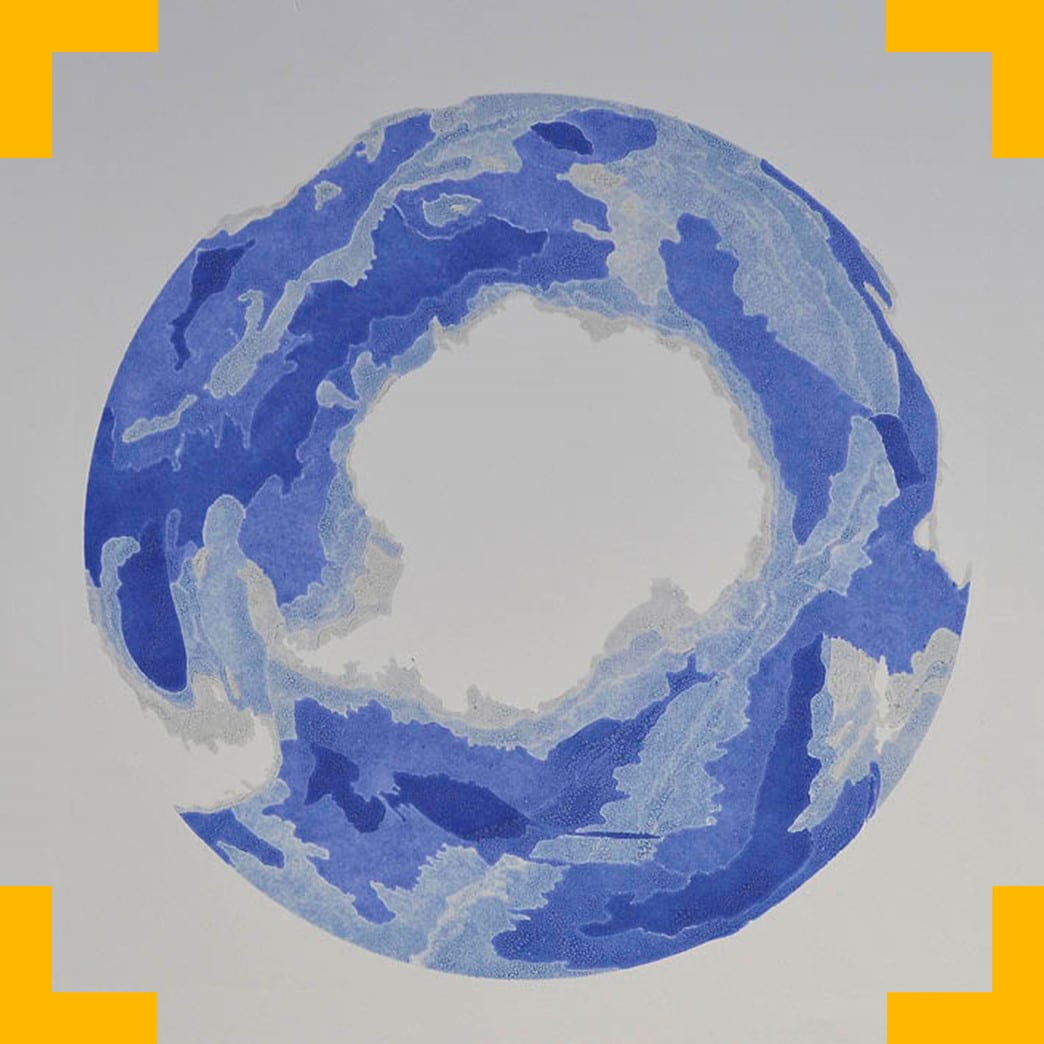

In 2017, the Cabot Institute and the Brigstow Institute hosted a variety of workshops on ‘Perspectives from the Sea’, bringing together scientists, engineers and humanities scholars to share personal reflections, their experiences and methods, and their understanding of the sea. This was so inspiring that we commissioned artist Rodney Harris to further explore these topics, The Invisibility of the Sea, displayed in the Earth Sciences Gallery. He produced a fantastic variety of pieces, including the one below.

As part of this, we assembled a working paper of perspectives. The following are two of my contributions.

I find Rod’s artwork to be profoundly moving, perhaps arising from my own complicated journey from the landlocked US state of Ohio to living on an island and devoting my life to understanding the nature and history of our mysterious oceans. I grew up on a dairy farm, about as far from the sea as you can get, physically and culturally. In particular, the daily and inflexible demands of dairy farming meant that vacations were rare, and I only saw the sea once or twice growing up. In those early days, Lake Erie was my analogue for the Invisibility of the Sea. I grew up with its history, from famous Revolutionary War battles to battles with pollution; I fished on Lake Erie with my Aunt and Uncle, even though we were cautioned not to eat too much of the perch and walleye that we caught; to pay my way through University, I studied invasive zebra mussels; and my family and friends went to ‘North Coast’ beaches for picnics and parties. But it was not the Sea. There was no vastness; there was no depth.

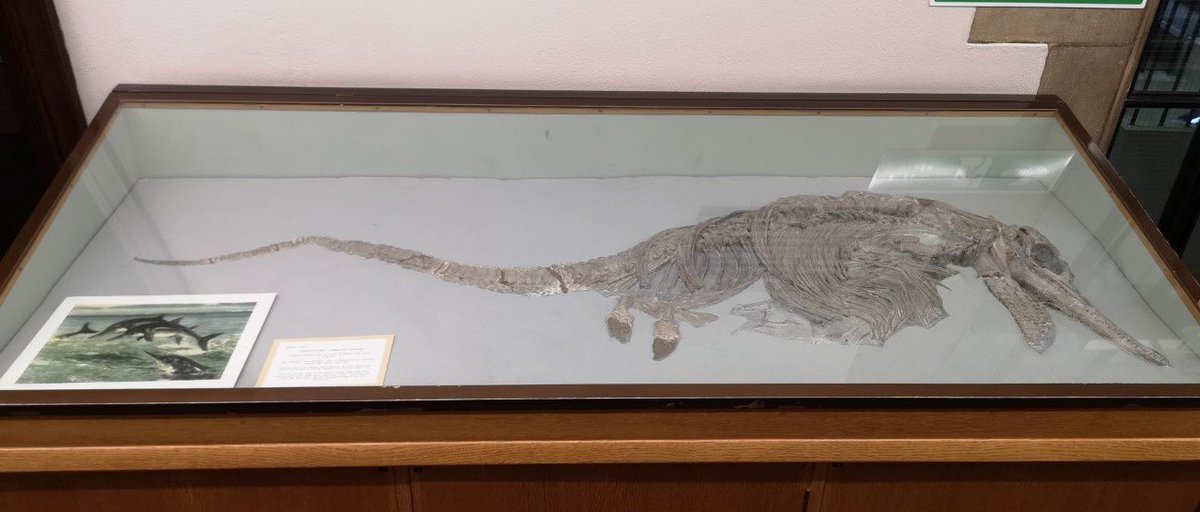

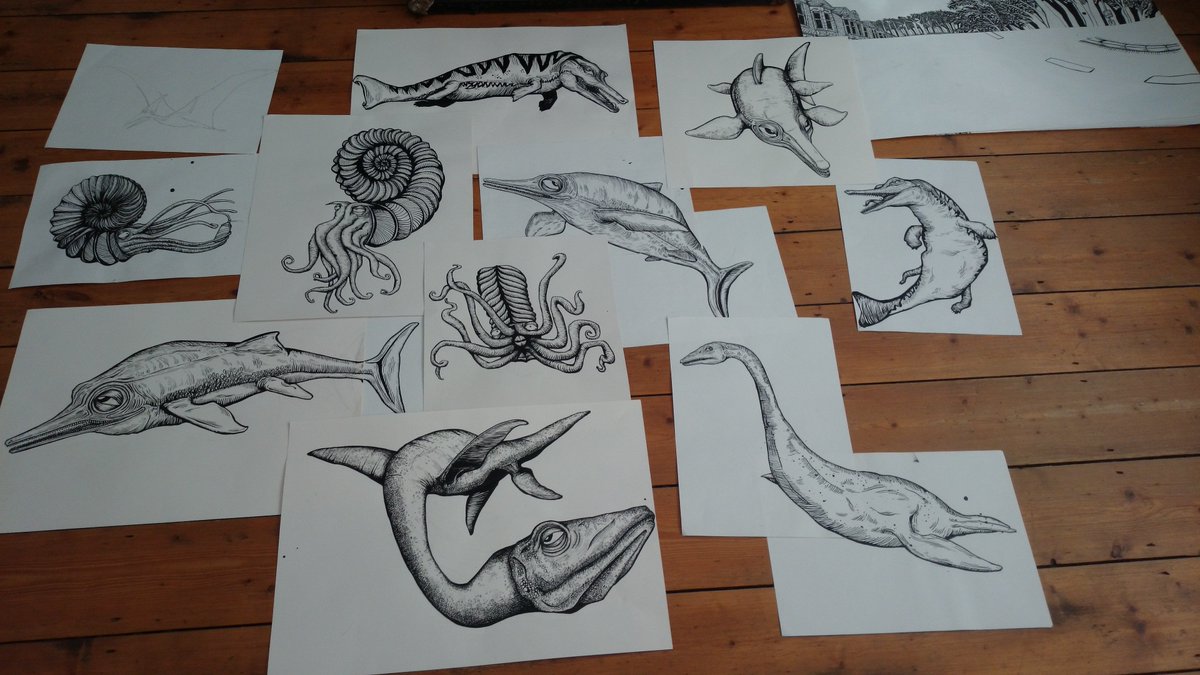

Ironically, my first profound relationship with the Sea came from going further inland, during my geology degree and PhD training and research. It was not the Sea of our modern world. It was the sea explored and imagined via the sedimentary rocks deposited in ancient oceans tens of millions of years ago. I studied and still study times of mass extinction, dramatic climate change or periods of profound chemical transformation, all manifested through the fossils – especially molecular fossils – produced in those ancient seas, buried in sediments and preserved in magnificent sequences of sedimentary rocks. Sometimes it seems that my work borders on the mythical as I study these ancient, secret seas that no longer exist. I study ammonites, belemnites and pleisiosaurs, cyanobacteria and thaumarchaeota, in ancient oceans such as the Western Interior Seaway, the Permian Basin, the Tethyan and Panthalassa Oceans, at locations such as Tarfaya, Zumaia and Lomonosov Ridge, at Kheu River and Waipara and Meishan.

This sense of mystery arises from time and space – the vastness of the ocean, its mercurial nature and its inscrutable depths, but also the billions of years of Earth history it records. It is why it is home to so many myths. Rod’s work captures the mystery and superstition with which ancient seafarers regarded the ocean – a place of ritual and norms, of sea serpents, mermaids and mythical beasts, of Odysseys. All of his ‘Balmoral Barometers’, especially but not only the Barometer of the Superstition of the Sea, capture our fraught relationships with this vast and seemingly unknowable body. And the vastness of the oceans and their invisible depths allow such myths to persist. We no longer believe that dinosaurs will be found in an isolated corner of the Amazon, but some still cling to beliefs that we will discover a buried Atlantis or prehistoric mega-sharks, 20-m long Miocene Megaladons still preying on giant squid or baleen whales in the great dark deep of the ocean.

This is the Invisibility that has always fascinated me. I have now been on research expeditions across our Seas and dived via submersible to the bottom of the Mediterranean. I am fascinated by both the surface and deep ocean and the different relationships we have with each. When we think of the ‘Sea’, I think we emotionally connect differently to its volatile surface and its infinite, mysterious depths. The surface is what we experience in trade, slavery, migration, travel, holiday snorkelling and exploration; this is what provides escape from persecution, threatens us with sea level rise, is the source of most of our fish, where sailors lose their lives; it is the network of ocean roads that support our global economy and sustained a global slave trade. In contrast, the deep ocean is vast, mysterious and constant – a home to krakens, hidden prehistoric sharks and lost cities but also limitless resources and room for waste.

More recently, however, it has become clear to me that for most of us all of the ocean remains invisible. We do not see the plastic or toxins in the ocean – plastics that now form islands of trash and can be found in every part of the ocean. We do not see the incremental but biologically devastating increases in temperature and decrease in pH due to increasing carbon dioxide in our atmosphere. We can measure those. But as a society we do not see them. The sea is invisible. Perhaps even more invisible now, despite our many scientific advances, than in the past when it was so intimately connected to our daily lives. This is where mystery meets apathy. Our assumptions, our view of the sea, are informed from earliest history, when only tens of millions of humans lived on the planet and our impact was small and could be absorbed, when a deep ocean could be a home to sea serpents and krakens and be a repository for our rubbish. On my first research expedition we discovered, half-buried in 2-km deep mud just north of Crete, a magnificent 2-m tall amphora but also plastic bottles: similar waste from separate millennia. Ingrained in us is the belief that the ocean is a great constant, impervious to human action.

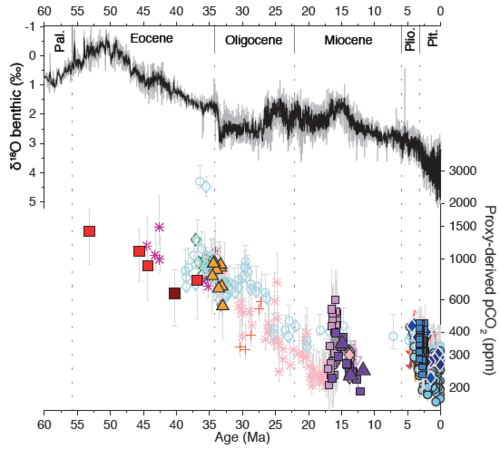

It is not. Those sedimentary records tell us otherwise. Its circulation can change; its chemistry can change; its biology can change. It is evident in Rod’s Brent Knoll, each colour made from a different bit of the sea’s sedimentary history and each representing a profound change in those ancient oceans. Although the oceans have been a constant during humanity’s brief domination of the planet, they can change. And now they are changing at a pace perhaps unprecedented in the history of our planet. Because of us.

We have allowed that to happen not because the sea is ‘invisible’ but because we have chosen not to see. But we are no longer allowed the privilege of blindness. Ocean warming is devastating our coral reefs, plummeting fish stocks are causing us to raid the ocean depths to feed our growing population, toxic blooms of algae kill fish and blight our beaches, and plastic… is everywhere. Much of the sea was invisible to our ancestors. We do not have that excuse.

The Invisible and Inconstant Deep Sea

Today, the deep sea is a dark and empty world. It is a world of animals and Bacteria and Archaea – and relatively few of those. Unlike almost every other ecosystem on our planet, it is bereft of light and therefore bereft of plants. The animals of the deep sea are still almost entirely dependent on photosynthetic energy, but it is energy generated kilometres above in the thin photic zone. Beneath this, both animals and bacteria largely live off the scraps of organic matter energy that somehow escape the vibrant recycling of the surface world and sink to the twilight realm below. In this energy-starved world, the animals live solitary lives in emptiness, darkness and mystery. Exploring the deep sea via submersible is a humbling and quiet experience. The seafloor rolls on and on and on, with only the occasional shell or amphipod or small fish providing any evidence for life.

And yet life is there. Vast communities of krill thrive on the slowly sinking marine snow. Sperm whales dive deep into the ocean and emerge with the scars of fierce battles with giant squid on which they feed. And when one of those great creatures dies and its carcass plummets to the seafloor, within hours it is set upon by sharks and fish, ravenous and emerging from the darkness for the unexpected feast. Within days the carcass is stripped to the bones but even then new colonizing animals arrive and thrive. Relying on bacteria that slowly tap the more recalcitrant organic matter that is locked away in the whale’s bones, massive colonies of worms spring to life, spawn and eventually die.

But all of these animals, the fish, whales, worms and amphipods, depend on oxygen. And the oceans have been like this for almost all of Earth history, since the advent of multicellular life nearly a billion years ago. This oxygen-replete ocean is an incredible contrast to a handful of events in Earth history when the deep oceans became anoxic. Then, plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs and mosasaurs, feeding on magnificent ammonites, would have been confined to the sunlit realm, their maximum depth of descent marked by a layer of bright pink and then green water, pigmented by sulfide consuming bacteria. And below it, not a realm of animals but a realm only of Bacteria and Archaea, single-celled organisms that can live in the absence of oxygen, a transient revival of the primeval marine ecosystems that existed for billions of years before complex life evolved.